Train Less, Think More

Empirical Categories

In brief, Large Language Models (LLMs) evolve through three main phases: they begin with a vast pre-training regimen, move into a period of refinement under reinforcement learning, and finally reach the stage of inference where users interact with them. Pre-training is where a model takes in huge volumes of text to acquire a broad understanding of language and facts — think of a person spending years studying in a library, but massively scaled up in terms not only of how much is read but also over what time. Consider, for example, 100+ billion parameter LLM will tyically take 3–6 months to train. Following which, reinforcement learning then shapes the model’s behaviour, guiding it with feedback from human or automated evaluators to produce responses that are not just accurate but also aligned with particular values. Finally, inference is where all that learning becomes tangible. Users ask questions or give prompts, and the model replies, drawing from everything it has absorbed while striving to stay helpful, safe, and on track.

Bigger is Better?

Progress in LLMs has hinged on scaling up train-time compute. The prevailing idea that bigger models trained on more data would yield better performance. But this arms race faces steep practical limits. Training increasingly massive models from scratch on billions or trillions of parameters pushes not only financial budgets but also hardware constraints to their breaking points. Key players like Microsoft and OpenAI, for example, are even establising deals for nuclear power generation to secure the energy resources needed for these computationally intensive operations. Hence, as training clusters skyrocket in cost, researchers are looking for ways to make better use of existing, or at least more modestly sized, models. This is where test-time compute scaling enters the conversation.

An article by researchers at Hugging Face, ‘Scaling Test Time Compute with Open Models’ (Beeching, Tunstall, and Rush, 2024) demonstrates how smaller models can still handle complex tasks by ‘thinking longer’ during inference. Instead of relying on a brute force approach — namely throwing more and more GPUs at pre-training — it is possible to deploy smarter strategies when the model is already trained and is being used in real time. The authors explore this concept in depth, effectively back-engineering OpenAI’s o1 model, which reportedly improves on math tasks when given more test-time processing.

Although we don’t know how o1 was trained, recent research from DeepMind shows that test-time compute can be scaled optimally through strategies like iterative self-refinement or using a reward model to perform search over the space of solutions. (Beeching, Tunstall, and Rush, 2024)

Although o1 itself is closed-source, the Hugging Face team (building on the DeepMind research) provide open-source methods to replicate and even surpass some of these improvements.

Test Time Compute

To appreciate what test-time compute scaling means, imagine you’re given a tricky math puzzle. You could either become an even more knowledgeable mathematician by studying for months (the train-time approach) or think a bit longer as you work through the problem in the moment (the test-time approach). Pre-training equates to years of studying; test-time compute strategies are more akin to the effort you expend while actually taking the exam. By carefully allocating extra ‘thinking time’ where it’s needed most, smaller models can rival — and occasionally outperform — bigger ones on challenging tasks such as the MATH benchmark.

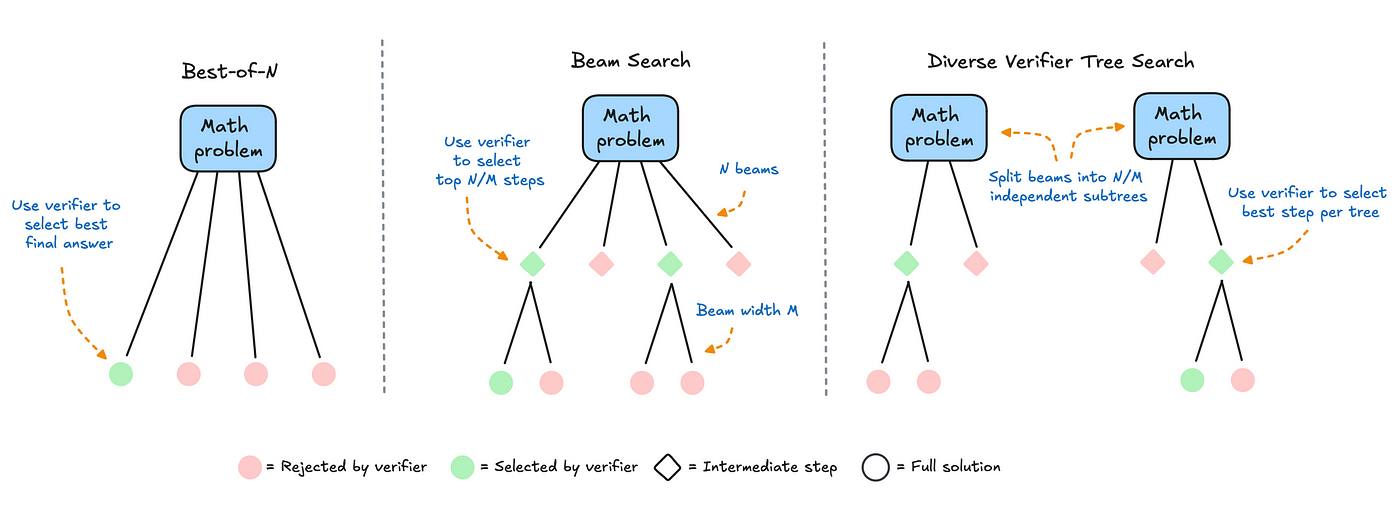

A key way to harness test-time compute is majority voting, or ‘self-consistency decoding,’ which involves sampling multiple answers and picking the one that appears most often. While this method works for certain tasks, it has limits. If a model systematically stumbles over a particular type of reasoning, sampling multiple times might not fix the root cause of the error. The Hugging Face article shows how to improve on majority voting with a technique called Best-of-N, in which a reward model ranks the candidate outputs. Instead of relying on the most frequent answer, you select the candidate that the reward model judges most plausible. This reward model can be a fine-tuned neural network specialized in evaluating the steps or the final answer itself — sometimes referred to as a process reward model (PRM).

The Hugging Face team then consider how to push this concept further with beam search, a structured strategy that expands multiple candidate solutions step by step. The PRM scores each partial solution, so the search systematically pursues the most promising lines of reasoning. Beam search often outperforms simpler decoding strategies, yet it can suffer from a lack of diversity when too much test-time compute causes the search to funnel into a single path. This prompts the authors to devise Diverse Verifier Tree Search (DVTS), which partitions the search into multiple subtrees so the model can explore different lines of reasoning in parallel. As the results show, beam search tends to work best for harder problems at smaller search budgets, but DVTS excels when there’s more compute available and the user wants to generate a broader range of solutions.

Compute-optimal Scaling

One of the most significant revelations is ‘compute-optimal scaling.’ Rather than picking a single decoding strategy for every problem, the idea is to adapt based on how difficult the prompt appears to be. Simpler tasks might benefit from, say, a quick Best-of-N approach. More difficult tasks might call for beam search or DVTS. By matching the best method to each problem’s difficulty, a smaller model can flexibly allocate just the right amount of test-time compute, circumventing the need for an ever-larger network. The end result is that models as small as one or three billion parameters can outperform larger ones — 70B in some cases — if they’re given enough time to explore their solution space effectively.

The Hugging Face authors close with several exciting directions. Verifier models that judge partial solutions more reliably can supercharge these search-based methods, but creating such robust verifiers is nontrivial. Another frontier is self-verification, where the model learns to critique its own thoughts, reminiscent of reinforcement learning with human or environment feedback. If a model can effectively detect its own mistakes on the fly, test-time compute could be allocated automatically in a loop of generating, checking, and revising solutions. It’s also possible that these search-based methods will expand beyond math problems or code to more subjective tasks if reward models can learn to evaluate content quality along axes like clarity, creativity, or cultural sensitivity.

Test-time compute scaling fits neatly alongside the pre-training, reinforcement learning, and inference pipeline. Pre-training and reinforcement learning set up what the model knows and how it behaves, but the final act of inference is where we can apply additional ‘smartness’ to get the most out of a given model size. It’s an alternative to simply building bigger and bigger networks, and it reinforces the notion that performance in AI can come from clever usage of resources as well as from brute force scaling.

Train Less, Think More

A shift is occuring, then, in how we think about AI development. Instead of blindly pushing for larger scale at train time, there’s a push to ensure that each query gets precisely the amount of computational reasoning it needs at inference. The synergy is powerful: a robust pre-trained model, refined through reinforcement learning, and then carefully ‘coaxed’ to produce its best answers by applying adaptive test-time strategies. Researchers and practitioners now have a broader repertoire for improving performance without spending a fortune on training. As the Hugging Face team underline, an open-source ecosystem for these methods is already emerging, providing both the conceptual ideas and the practical code to implement them.

In short, the life of a large language model doesn’t end when it finishes pre-training or even reinforcement learning. A new frontier of test-time compute scaling has arrived, allowing smaller models to match or beat bigger ones on complex tasks by selectively thinking longer. This approach holds promise not just for math problems, but for any domain where carefully verified reasoning steps matter. By weaving these methods into the final stage of inference, every question ideally gets a worthy answer, all while keeping large-scale compute budgets in check.