Interview with Lévi-Strauss (1967)

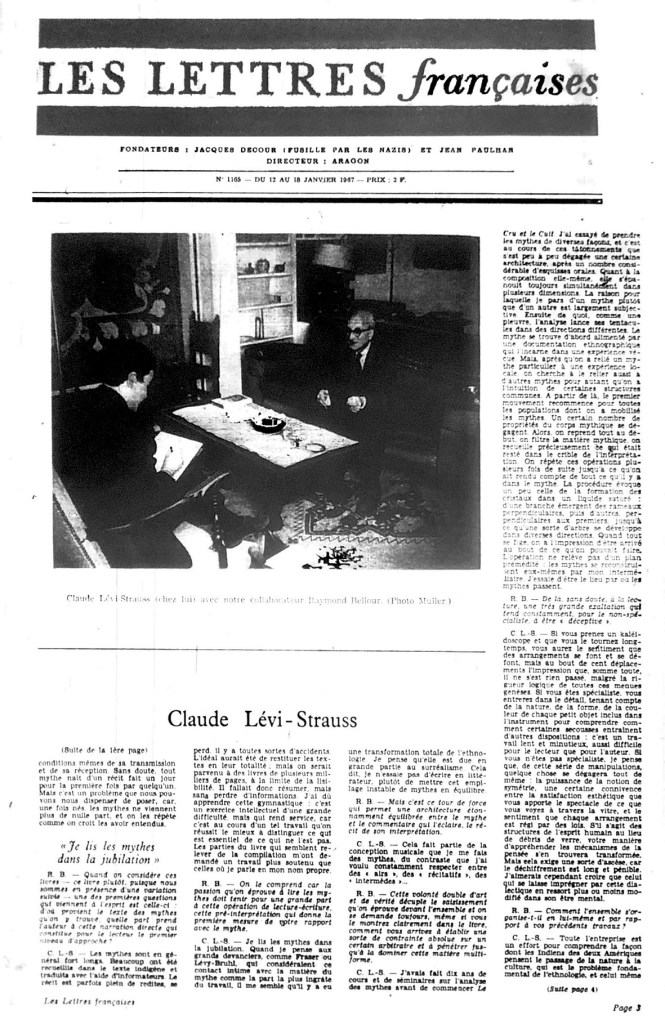

The following text is a LLM (Claude Sonate 3.5) translation of an interview with Claude Lévi-Strauss from 1967, published in Les Lettres françaises. The interview, along with another follow-up interview in 1972, was conducted by Raymond Bellour. Both interviews are ‘a sort of work-in-progress report on the different volumes of the Mythologiques cycle, which appeared over a seven-year period, between 1964 and 1971’*. They offer an informed, specialised dialogue on Lévi-Strauss’ project.

* C. Johnson (2003) ‘Lévi-Strauss in his Interviews’, Nottingham French Studies, Vol. 42, No.1, pp.33-47.

Interview with Claude Lévi-Strauss

How the Human Mind Works

Les Lettres françaises (No. 1184. January 12-18, 1967, pp.1-7)

RAYMOND BELLOUR: How do you situate this research you’ve undertaken under the title ‘Mythologiques,’ which, inaugurated by The Raw and the Cooked, continues today with From Honey to Ashes before proceeding further in two upcoming volumes?

CLAUDE LÉVI-STRAUSS: As with everything I’ve attempted to do, it’s about understanding how the human mind works. I chose to study South American mythology for several reasons. First, because I know it. Then because I believe it to be quite beautiful, and it’s fitting to make it accessible and interpret it. Finally, I chose this problem because it has too often been believed that in mythology, man gave free rein to his creative fantasy and that it was thus arbitrary. However, if we manage to show that even in this domain, which has a limiting character, there is something that resembles laws, we can conclude that they also exist elsewhere and perhaps everywhere.

RB: I suppose the limitation of your field of study is closely linked to the inductive intention of your approach.

CLS: It was necessary to avoid the old abuses of comparative mythology, which was content with superficial analogies to compare anything with anything. I wanted to do an in-depth analysis of a vast but limited domain, where we can postulate and prove that in addition to the similarities specific to mythical thought, there is a whole network of deep, historical, and geographical relationships that underlie the analogies. But if the method is worth anything, it also allows us to reach foundations that go beyond the South American framework and access a general experience.

RB: What do you mean by that?

CLS: A sensible experience that man can acquire of the mechanisms of his thought. Mythology is one of the ways in which one can attempt it, but it’s not the only one. I’ll go further: if the method I’m trying to apply is valid in mythology, it should be usable for other forms of human mental activity such as poetry, music, and painting. Mythology represents a privileged case, because of the very conditions of its transmission and reception. Undoubtedly, every myth is born from a story told for the first time one day by someone. But that’s a problem we can dispense with, because once born, myths no longer come from nowhere, and they are repeated as one believes to have heard them.

RB: When one considers these books—this book rather, since we are in the presence of a continuous variation—one of the first questions that comes to mind is this: where does the text of the myths found in it come from, what part does the author take in this direct narration which constitutes for the reader the first level of approach?

CLS: Myths are generally very long. Many have been collected in the indigenous text and translated with the help of informants. The narrative is sometimes full of repetitions, gets lost, there are all sorts of accidents. The ideal would have been to restore the texts in their entirety; but we would have ended up with books of several thousand pages, at the limit of readability. It was therefore necessary to summarize, but without losing information. I had to learn this gymnastics: it’s an intellectual exercise of great difficulty, but it’s useful, because it’s during such work that one succeeds best in distinguishing what is essential from what is not. The parts of the book that seem to be compilation required more sustained work from me than those where I speak in my own name.

RB: One understands this because the passion one feels when reading the myths must be largely due to this operation of reading-writing, this pre-interpretation, which gives the first measure of your relationship with the myth.

CLS: I read myths with jubilation. When I think of the great predecessors, like Frazer or Lévy-Bruhl, who considered this intimate contact with the material of myth as the most thankless part of the work, it seems to me that there has been a total transformation of ethnology. I think it’s largely due to surrealism. That said, I’m not trying to write as a man of letters, rather to put this unstable pile of myths in balance.

RB: But it’s this tour de force that allows for an amazingly balanced architecture between the myth and the commentary that illuminates it, the story of its interpretation.

CLS: That’s part of the musical conception I have of myths, of the contrast I wanted to constantly respect between “airs,” “recitatives,” “interludes”…

RB: This dual will of art and truth increases tenfold the amazement one feels before the whole, and one always wonders, even if you show it clearly in the book, how you manage to establish a sort of absolute constraint on a certain arbitrariness and to penetrate to the point of dominating this multiform matter.

CLS: I had given ten years of courses and seminars on the analysis of myths before starting “The Raw and the Cooked.” I tried to approach myths in various ways, and it was during these gropings that a certain architecture gradually emerged, after a considerable number of oral sketches. As for the composition itself, it always unfolds simultaneously in several dimensions. The reason why I start with one myth rather than another is largely subjective. After that, like an octopus, the analysis extends its tentacles in different directions. The myth is first fed by ethnographic documentation that embodies it in a lived experience. But, after connecting a particular myth to a local experience, we try to connect it also to other myths insofar as we have the intuition of certain common structures. From there, the first movement begins again for all the populations whose myths we have mobilized. A certain number of properties of the mythical body emerge. Then, we start all over again, we filter the mythical material, we carefully collect what was left in the sieve of interpretation. We repeat these operations several times in a row until we have accounted for everything in the myth. The procedure is somewhat reminiscent of the formation of crystals in a saturated liquid: from one branch emerge perpendicular twigs, then others, perpendicular to the first ones, until a sort of tree develops in various directions. When everything sets, one has the impression of having reached the end of what one could do. The operation does not follow a premeditated plan: the myths reconstruct themselves through my intermediary. I try to be the place through which the myths pass.

RB: Hence, no doubt, in reading, a very great exaltation which tends constantly, for the non-specialist, to be “deceptive.”

CLS: If you take a kaleidoscope and turn it for a long time, you will have the feeling that arrangements are made and unmade, but after a hundred shifts, the impression that, all in all, nothing has happened, despite the logical rigor of all these minute geneses. If you are a specialist, you will go into detail, taking into account the nature, form, and color of each small object included in the instrument to understand how certain shocks lead to other arrangements: it’s a slow and meticulous work, as difficult for the reader as for the author. If you are not a specialist, I think that, from this series of manipulations, something will still emerge: the power of the notion of symmetry, a certain connivance between the aesthetic satisfaction that the spectacle of what you see through the glass brings you, and the feeling that each arrangement is governed by laws. If it’s about the structures of the human mind instead of glass debris, your way of apprehending the mechanisms of thought will be transformed. But this requires a kind of asceticism, because the deciphering is long and painful. I would like to believe, however, that the one who allows himself to be impregnated by this dialectic comes out more or less modified in his mental being.

RB: How does the whole organize itself internally and in relation to your previous work?

CLS: The entire enterprise is an effort to understand how the Indians of the two Americas think about the passage from nature to culture, which is the fundamental problem of ethnology, and indeed of any philosophy of man. In “The Elementary Structures of Kinship,” I had tended to consider that the nature-culture opposition was part of the order of things and expressed a property of reality. I have evolved quite a bit since then under the influence of progress in animal psychology and the tendency to introduce cultural notions into the natural sciences: for example, that of genetic information in biology or game theory in physics. Today, the nature-culture opposition seems to me less to reflect a property of reality than an antinomy of the human mind: the opposition is not objective, it is men who need to formulate it. It may constitute a prerequisite for the birth of culture.

It seemed to me that, among South American Indians, this opposition was mainly expressed by the relationship between the raw and the cooked, which provided the argument for the first volume. A confirmation has just been provided by an American colleague who knows the language of these populations. He noted, in fact, that among them, any passage from one social status to another is called by a word that means “cooking.”

But at the same time as I was exploring this universe, I perceived that the notions of raw and cooked were not sufficient to exhaust it since there exists “less than raw” and “more than cooked”: that’s how I stumbled upon honey on the one hand, and tobacco on the other. In recognizing these surroundings, I saw other propositions appear that are situated on two levels:

First, honey and tobacco do not illustrate static states like the raw and the cooked, but dynamic imbalances. The significance of honey translates a perpetual descent towards nature, that of tobacco an ascent towards the supernatural.

Secondly, myths that were defined in terms of space by the opposition of high and low, of sky and earth, are now defined in terms of time. Thus the problem of periodicity is introduced. Finally, and above all, I saw appear, behind the logic of sensible qualities, a more fundamental logic, a logic of forms.

This is the dialectical movement that links the two volumes: the passage from a spatial mythology to a temporal mythology, and from a logic of sensible qualities to a logic of forms.

The third volume will be entirely devoted to mythical representations of periodicity. We will attempt to show how indigenous thought thematizes the continuous and the discontinuous in the order of time. But at the same time, another change will occur: myths that were analyzed in the first two volumes from the angle of cuisine and the surroundings of cuisine will be analyzed here from the angle of good manners. This third volume will probably be titled: “The Origin of Table Manners.” And it will lead to a morality implicit in the myths.

RB: And the fourth volume?

CLS: Another phenomenon occurs in the third volume. We arrive at the very limits of the intelligibility of a mythical system. To interpret certain South American myths on which local material does not shed light, we must “expand the paradigm” and look towards North America. This opening movement is therefore twofold: from culinary techniques to domestic morality, from South America to North America. Consequently, the fourth volume will be devoted to North America where I find the same myths that served as a starting point for “The Raw and the Cooked,” transformed however due to the change of hemisphere and differences in terms of economy and techniques. The journey will come full circle; we will find in the northern regions of North America the equivalent of what we observed in the heart of South America. It will appear at the same time that the ultimate reason for the differences between myths that all belong to the same genre lies in the infrastructures, in the sense of the relationships that each human society maintains with its environment.

RB: As resolutely as you remain in time and space in a domain circumscribed to the Indians of America, you nevertheless attempt more or less numerous and prolonged “excursions,” in “The Raw and the Cooked” for example, towards French customs for your analyses of the “charivari” and astronomical semantics, in “From Honey to Ashes” towards Oriental mythology through the very beautiful Japanese myth of the “crying baby” as you already did in “Structural Anthropology” about the Oedipus myth. Do you attribute an exemplary value to these multiple incursions and do they tend to suggest the idea that mythology could be interpreted in terms of a single structure?

CLS: I leave the question open and don’t prejudge: are there several mythologies or just one? We’ll see. The incursions I allow myself have a dual character. First of provocation: I would like to encourage people working in other fields to ask questions in the same terms, without suggesting the answer to them. Then and above all, from time to time and in privileged cases, I have the feeling of approaching fundamental truths, of having touched rock bottom. It is then important to do a quick survey in a very different domain, which constitutes a sort of control experiment.

RB: You have been variously criticized for your attitude towards history. Roger Garaudy, for example, in “Marxism of the 20th Century,” deplores the theoretical break between the method of ethnology and that of history; for his part, Sartre still affirmed, in the recent issue of L’Arc devoted to him, that structuralism as you practice and conceive it “has greatly contributed to the current discredit of history.”

CLS: I deal with societies that do not want there to be history: that’s their problematic. They do not want to be in historical time, but in a periodic time that cancels itself out like the regular alternation of day and night. That said, I do not at all have the negative attitude towards history that is attributed to me. Among the partisans of what one might call “history at all costs,” I only fear a mysticism and an anthropocentrism that put their problematic above all others. About history, one must always ask whether there exists a single one capable of totalizing the entirety of human becoming, or a multitude of local evolutions that are not justiciable of the same design. That at one point on the inhabited Earth, at a certain time, history became an internal motor of economic and social development, I’m willing to accept. But this is a category internal to this development, not a category co-extensive with humanity. One can generally accept the Marxist point of view on what happened in Western Europe from the 14th century to our days. But should it apply to all phases of human becoming? I don’t think so, nor did Marx, who said it many times.

When an architect destroys or builds a house — and I use this image to preserve the rights of revolutionary activity — he makes an act of faith in Euclidean geometry, but it ceases to be true in orders of magnitude incommensurable with that one. To want to demand that what may be true for us be true for all and for all eternity seems to me unjustifiable and to fall under a certain form of obscurantism. It’s a theologian’s attitude, and the history of philosophy is not lacking in such examples. I would like a more relativistic attitude to be observed in the human sciences. But one senses in some a desire to keep philosophy’s control over research that is trying to become positive, and which is not bothered by the fact that research simultaneously borrows paths that sometimes seem contradictory to each other while proving their particular effectiveness. This is the profound origin of the misunderstanding that opposes me to certain philosophers: as I reject their problematic for my domain, they imagine that I claim to extend mine to theirs, for they do not conceive that one can change perspective according to the levels one considers in reality.

RB: But isn’t the domain of philosophy precisely to have none and to think about all of them?

CLS: Philosophers, who have so long enjoyed a sort of privilege because they were recognized as having the right to speak about everything and on all occasions, must begin to resign themselves to the fact that many areas of research are escaping philosophy. I’m not saying definitively, forever, because perhaps they will return to it — it would be an act of faith in history to affirm the opposite — but we are witnessing a kind of fragmentation of the philosophical field. Maintaining all-or-nothing demands would result in sclerosing the human sciences.

RB: You say: “things outside of philosophy.” When these things are perhaps the essential, it is in fact leaving philosophy only the obligation and the possibility of its own history.

CLS: That’s a problem for philosophers and not for me. It doesn’t seem to me that philosophy has universal jurisdiction in every epoch.

RB: What do you think of the current tendency to bring together disciplines that, in various fields, openly claim structural methods? Are we witnessing, in your opinion, an impact that would justify an extensive and defined use of the word “structuralism”?

CLS: I don’t have that impression. You’re probably thinking of the journalistic tic that consists of associating Lacan’s name and mine; I imagine that must surprise him too. Our enterprises seem divergent to me, because if one moves away from philosophy, the other leads back to it. It’s true that the rules of deontology forbid psychoanalysts from restoring their experience as clinicians in its concrete richness. The monograph is a difficult genre for them, while it provides the essential material for our studies, and it is always available to check the validity of theoretical hypotheses. The ethnologist feels more at ease with these singular objects that are societies localized in time and space, observed at different dates by several investigators and whose customs, beliefs and institutions offer themselves to him in a somewhat solidified form. He never asks to be believed on his word.

RB: So you have no impression of real convergence?

CLS: Only between ethnologists and linguists. We have the conviction of working in very intimate communion. Myths are above all linguistic beings, and since the means of control available to linguistics are superior to ours, we willingly place ourselves under its allegiance. Like linguists, we study particular beings, and that is undoubtedly what brings us closest together. For linguistics became positive when it ceased to speculate abstractly on the nature of language and began to study concrete languages.

RB: In the preface to “The Raw and the Cooked,” you evoke the “science of myths” of which your work would be only a sketch, and thus the ulterior necessity of a logico-mathematical analysis that suggests, among other things, the idea of a mechanical intervention. Have there been any experiences of this order to date?

CLS: There is an ongoing experiment at Harvard to process myths on a computer, which happen to be the same ones I worked on. It’s striking to see that, for the moment, artisanal methods – to the credit of humans – are faster than machines. But that won’t last. The time will come when the machine will beat me!

RB: How do you conceive the relationship between structuralism as you understand it and literary criticism?

CLS: You’re likely aware that, in collaboration with Roman Jakobson, I attempted to apply structural analysis to a Baudelaire sonnet. This work went almost unnoticed. I even believe that specialists suspected it of being a hoax. However, we ourselves took it very seriously, and in a book he has just completed, Jakobson extends the method to all sorts of poetic examples borrowed from different languages and civilizations.

Nevertheless, I hardly recognize the structuralist inspiration in most of the literary criticism endeavors that claim to follow it. Just as there can be no structural analysis of myths possible without constant recourse to ethnography, I cannot conceive of studying a literary work in a structuralist spirit without first securing all the resources that history, biography, and philology can provide for interpretation.

Moreover, if one can claim to rigorously understand the creations of the human mind, it is insofar as they offer the character of closed objects. To speak of an open work is to engage in a completely different direction. The proponents of the New Criticism constantly oscillate between two conceptions of the work, seeing it either as a construction, very complex no doubt, but whose internal properties and structure are as strictly fixed as, say, those of a large organic molecule, or on the contrary, as a sort of Rorschach test image that has no meaning of its own except those that each era or each reader projects onto it. Only the first conception falls within structuralism, but one passes from one to the other without even realizing that they are incompatible.

In my eyes, therefore, the opposition between old and new criticism is largely artificial. The structural study of literary works brings great insights, but these complement and renew without abolishing those that could be obtained by more traditional means. In terms of mythical analysis, whenever I can illuminate my object with historical, psychological, or even biographical information about the storyteller, I am not hindered but powerfully aided. If these various approaches seem hybrid, sometimes even contradictory, it’s because in the human sciences, we are still in our infancy. But research that aims to be positive does not exclude; rather, it makes use of every available tool. The debate surrounding the new criticism testifies once again that in our circles, nothing is more urgent than to deliver any newly opened domain to the encroachments of pseudo-philosophical verbiage.

RB: One senses, however, in everything you write, a sort of impatience for knowledge, in its philosophical sense, which corresponds on the other hand to the great diversity of cultural incursions we were talking about earlier.

CLS: It is clear that we are all more or less philosophers, that we cannot help but anticipate the normal course of our endeavors, and that to this extent, we engage in philosophy that can remain local, partial, provisional, without feeling committed by its own approaches. It thus fulfills a real function, but one that knows how to remain modest.

RB: What you call in “The Raw and the Cooked” “small-scale poaching.”

CLS: If you like. I don’t claim to give a total explanation. I am quite ready to admit that there are, in the whole of human activities, levels that are structural and others that are not. I choose classes of phenomena, types of societies, where the method is profitable. To those who tell me: “There is something else,” I can only answer: “Very well. You’re free to pursue that.” I only ask that one does not rush into dogmatism. One does what one can where one can. If one will concede to me that after “The Elementary Structures of Kinship,” we understand a marriage rule better than before, after “The Raw and the Cooked” and “From Honey to Ashes,” we understand a myth better than before, I am satisfied and do not demand that one immediately draw definitive conclusions about the ultimate nature of the human mind. I hope to make a modest contribution, to add pieces to an immense dossier. But it would take hundreds of researchers working on parallel paths for decades. Perhaps then something solid will emerge.

Either we will succeed in observing this attitude in the human sciences, or there will be no human sciences. I don’t want to show anti-philosophy. But we are currently grappling with a sort of theological humanism. Throughout the period when science was forming, people said: what you propose with your science calls into question the existence of God. Now we are told: it calls into question the existence of man. Recognizing that the earth revolves was not for Galileo to confess a metaphysical truth, but to make a local observation devoid of any pretension.

RB: Finally, I would say that one also senses in your “Mythologiques,” and even sees unfolding largely, a will for organization, for aesthetic expression, which articulates with the scientific approach, as if art were engaging in a more direct dialogue with science than that of philosophy.

CLS: Yes, but in both cases on the condition of putting them in perspective. It is not ethnography that provides a means of access to philosophy, but philosophy that serves me as a means, for it is one of the languages our civilization speaks to introduce the analysis of experiences that are foreign to us. Similarly, if I willingly introduce old engravings into my books, it’s because they express an aspect of myth in the same way that logico-mathematical formulas express other aspects. If myth possesses its own reality, it resides in this union of the sensible and the intelligible. Nothing, therefore, is foreign to myth. Even Riou’s drawing constitutes a variant of the myth, like those I could borrow from neighboring populations. And at the other end, the logico-mathematical formula is also an integral part of the myth. The problem is to place oneself at a point where nothing is lost on either side, to provide the means for a perpetual back-and-forth between anecdote and philosophy, aesthetic emotion and logical evidence. Curiosity about myths arises from a very deep feeling whose nature we are currently unable to penetrate. What is a beautiful object? What does aesthetic emotion consist of? Perhaps this is what, in the final analysis, through myths, we are confusedly trying to understand.

RB: The myth, then, would be, par excellence, the ethico-aesthetic object, the living idea of the absolute.

CLS: Perhaps; but this absolute would still be relative, for it would be defined in relation to the human mind which, in myth, simultaneously puts all its means into operation.

Afterword

“Oh, what power humans have to forge myths for themselves!” — Freud

It has been said — and the astonishing progression of his “Mythologiques,” which must be recognized, in the most anciently exact sense, as his masterpiece, will only incite us to say it again with more rigor — of what new authority Claude Lévi-Strauss’s work endowed the ethnographic science to which he has devoted his life, and to what extent this local revolution, whose methodical advance leads to the origin of the conditions of thought, proved essential to the elaboration of a science of man by marking most closely the impossibility or the present obligations of philosophy. Claude Lévi-Strauss illuminates here, as he does more learnedly, more indirectly also, in each of his books, the ambiguities that make his research valuable, he allows us to clearly recognize the exemplary nature, at once unlimited and limited, of a work whose most precise evocation is found, I believe, in the turn of a page of his latest work1. “As the investigation widens and new myths impose themselves on attention, myths examined long ago rise to the surface, projecting neglected or unexplained details, but which one then realizes are like those pieces of a puzzle, set aside until the almost completely finished work outlines in hollow the contours of the missing parts and thus reveals their obligatory location, from which results — but in the manner of an unexpected gift and an additional grace — the meaning, which remained indecipherable until the ultimate gesture of insertion, of a vague form or a degraded coloring whose relationship to neighboring forms and colors discouraged understanding no matter how one strove to imagine it.” Too little has been said, on the other hand, of all that such thoughts and words made one sense in their multiple depths, and how much this operation of knowledge whose rigor, once past the frontier of the exact sciences, encounters few examples, played a serious and learned game with the truth of art, the idea, the reality, even of literature.

For Lévi-Strauss, who arranges myths, stages in the double reversible space of the narrative and its documented interpretation the organic totality of a world; he thus assumes a task of heroic, social and cosmogonic representation that is born with literature in the form of myth and continues in the infinite mutations of the novel, in every narrative, maintaining with science an equivocal dialogue, full of gaps and attractions, to come and break diversely in the present impossibility of modern narrative abstraction. Now this is precisely what science, in its new forms, comes to take up again on its own account in one of the most spectacular inversions when in these “Mythologiques” it gives us to live, through a science of fiction, a living totality. Never has life possessed in a sense more real turbulence than in this play of vegetable and animal nomenclature and socio-cosmological law that articulates the tables of “The Savage Mind” and the relations of “The Elementary Structures of Kinship” in a vast logic of the sensible whose most constraining originality is to inversely establish a fiction of science that ensures the reciprocity of elements and principles, united according to an orchestration that comes to respond throughout the volumes to the analogy introduced by Lévi-Strauss in the beautiful “overture” of “The Raw and the Cooked,” between the mythical object and the musical object. The book, thus, chosen place of a combinatory and deployment of a rhythm, develops in a single operation the truths of science and art in the space of interpretation. “In its own way, a myth,” as the author wants it, myth among myths, since it assembles the infinity of stories in a single story, it is a logical narrative of savage thought.

This is why, strangely, these “Mythologiques,” where the impersonal reason of science blossoms in the most subjective and necessary of forms, are the closest in this work to the book most personal of all: “Tristes Tropiques.” As if, in the space of the narrative, analysis and autobiography found their common place, deepening each other in an indefinite series of relationships and detours that allow us to better understand the systematic experience of the modern hero where myth, as soon as it is formulated and in order to be so, splits on itself, doubles and recomposes itself infinitely. In this, Lévi-Strauss is very close to Freud whose experience he radicalizes through an extreme concern for logification that dissipates the image of the subject in an even more indirect form of autobiography, where the author disappears under the unheard-of variety of the world rediscovered by the power of the mind in a new kind of anonymity which is the sign of our greatest distance from mythical thought. It is not the least paradox of this time to see reborn, from the precise, radical experience of knowledge, and to serve it to the extreme, literature in its oldest reality: to the point where one wonders if the logified cosmogony, which comes to respond in Lévi-Strauss to savage thought as analytical interpretation responds in Freud to the epic adventure of the subject, would not be our myths the essential of this power that literature has too much lost to be able to narrate.

– Raymond Bellour

(1) Mythologiques II: From Honey to Ashes (Plon).