The Art of Coding

In order to pursue the objectives of a structuralist approach to AI it is pertinent to gain a more hands-on understanding of computer coding. As such I have established a supplementary ‘project’, The Art of Coding →

At root, the aim is to learn to code Python so as to be able to (a) ‘think like a computer scientist’ and (b) to undertake some of my own developmental coding. The project involves using a custom ChatGPT, The Art of Coding, which acts as a Python ‘tutor’. A key text associated with the GPT is the book How to Think Like a Computer Scientist (PDF version). In essence, this book is a ‘how to’ guide for those wanting to learn to programme in Python. Nonetheless, it offers a nuanced blend of step-by-step training and conceptual thinking, making it an excellent supplement to the overall project here of exploring the historical development of cybernetics and contemporary data science. The book, then, provides the structure and framing for a ‘course’ in learning to code. It also offers some wider philosophical considerations, which the GPT is instructed to amplify. A step-by-step approach of working with the GPT to learn to code is presented via a Google Colab Notebook. The idea is document the process akin to a diary, albeit not as regular collection of writings, but rather as a set of experiments in code – ideally giving rise to a collection of incrementally more complex programmes.

At stake is the proverbial ‘Two Cultures‘ problem, whereby misunderstandings are said to persistent between the sciences and the arts and humanities, due to a lack of shared knowledge and training. In order to help bridge this divide, the project sets the objective to simply learn a new skill and by extension to engage directly with a different knowledge base: computing coding. While the undertaking cannot be comprehensive, nor necessarily successful, the aim is to acquire a sufficient degree of understanding and appreciation for programming to change the level of engagement and writing represented by the Structuralism and AI project overall.

Typically, as noted in How to Think Like a Computer Scientist, ‘the first program written in a new language is called Hello, World! because all it does is display the words, Hello, World!’. In Python, the script reads simply as:

print(“Hello, World!”)

This is the literal starting point for this project, being both the simplest of programmes and a declaration from a non-coder seeking to say ‘hello’ to a whole new world(-view). Of course, in the manner of the ingenious ‘constructors’ of The Cyberiad (1965), the exploits of this project will likely reveal that the devil is always in the detail (of code). And like the tireless, yet maddening pursuits of Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet, the project is likely to raise far more questions (and new beginnings) than answers!

‘Once upon a time Trurl the constructor built an eight-story thinking machine. When it was finished, he gave it a coat of white paint, trimmed the edges in lavender, stepped back, squinted, then added a curlicue on the front and, where one might imagine the forehead to be, a few pale orange polkadots. Extremely pleased with himself, he whistled an air and, as is always done on such occasions, asked it the ritual question of how much is two plus two’. – Stanislaw Lem, The Cyberiad (1965).

§

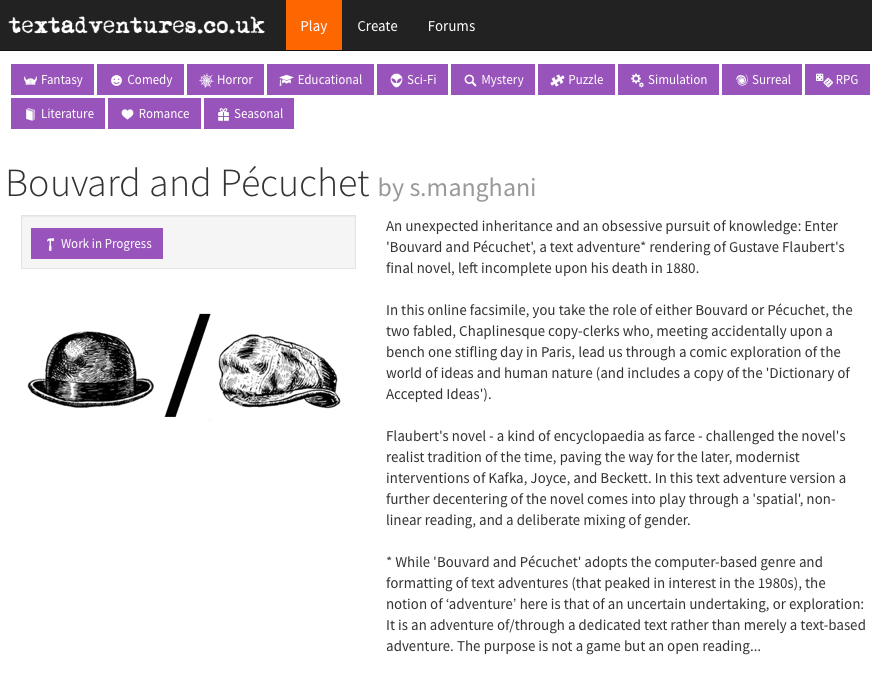

Bouvard and Pécuchet

An initial foray into the world of programming began during the UK’s covid lockdown, with a failed endeavour to render Gustav Flaubert’s final novel, Bouvard and Pécuchet (1881) into the form of an online text adventure game. For for anyone who knows the novel, the game sought to metonymically repeat the continual failed exploits of the novel’s two protagonists (see below). Hence, the ‘failure’ of the project was always actually intended, with its undoing to be deliberately built into the game from the start.

Flaubert described the novel as ‘a kind of encyclopaedia as farce’. At its core is a critique of the 18th and 19th century pursuits to catalogue, list and record all scientific and historical knowledge. Unfinished at the time of his death in 1880, Flaubert tells the tale of two Chaplinesque copy-clerks, Bouvard and Pécuchet, who meet one day at a park bench in Paris and strike up an immediate friendship. After Bouvard receives a generous inheritance, they give up work, move to the countryside and together explore the ‘world of ideas’. The tale of their exploits, in seeking restlessly yet apparently methodically to learn one area of knowledge after another, provides a penetrating exploration of the relation of signs to the objects, and the systematic confusion of signs and symbols with reality. Bouvard and Pécuchet’s persistent failure to learn from their adventures raises a question about what is knowable (on the rare occasions they do achieve a modicum success, it is largely down to unknown external forces beyond their comprehension). By the end of the novel, having tired of the world in general, Bouvard and Pécuchet dispense with their intellectual endeavours, favouring instead a return to the work of copying. While the story remains incomplete, we hear of their keen preparations to construct a two-seated desk at which to write. Here, we are led to believe, they ‘copied out’ The Dictionary of Received Ideas (an encyclopedia of commonplace notions).

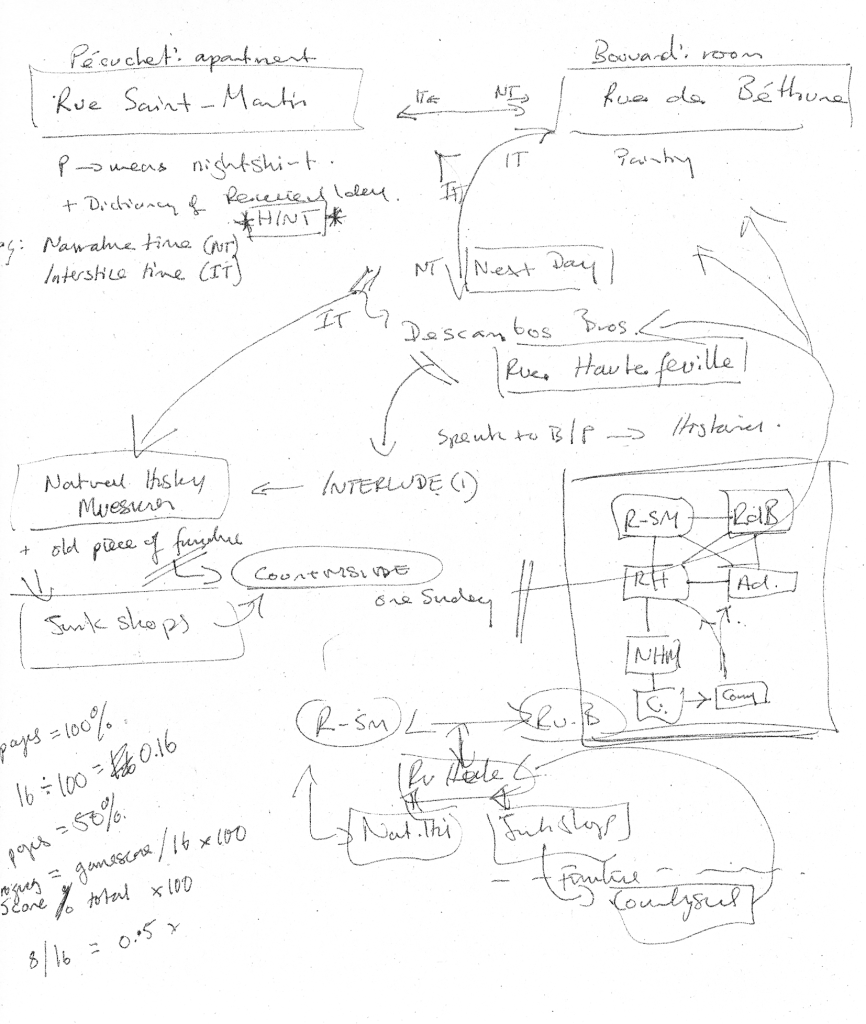

What the text adventure game version sought to do was re-invest the novel with an experiential account of the characters and the world they inhabit. You can move from one location in the novel to the other as you wish. And so, while the adventure game version retains the ‘linear’ story of the novel, in other words it takes you through the text in a sequence that follows the book, you can still move the characters from one location to another, and you can perform simple actions at will, such as talking to other characters, picking up and examining objects and even just choosing to ‘wait’, allowing time to pass (or at least the semblance of time). In this way, the game captures some of Lord B.’s reminiscence in playing of early computer text adventure games: ‘I never tired of watching the scroll upon the screen and I was enthralled with how you could traverse the landscape of these words, typing commands to ‘go north’ or ‘enter room’.

However, in the manner of Bouvard and Pécuchet themselves, the undertaking in the programming itself was far too elaborate from the start. An online software, Quest, allowed for an essentially Boolean approach to coding the game. At the backend, the coding is full of logic gates (‘if x…’, ‘if not x… then…’, ‘if x and y… then…’ etc.), which becomes increasingly layered as you allow for the player to move at between the other linear nature of the text from the original novel (which requires a certain chronology to allow the narrative to unfold). Matters were only exacerbated an attempt to update the novel, enabling the player select from three gender positions. Given the game can be played from either the point of view of Bouvard or Pécuchet, and with three gender positions, the complex enough coding for the narrative unfolding is layered six-fold. There are numerous freely available softwares for building ‘interactive fiction’, which would have made the job much easier, but, these restrict to a simple narrative unfolding, rather than allow for both a temporal narrative and a ‘spacial text’.

In the event, it took many months to render only chapter one of the novel, and with potentially even greater complexities on the horizon if pursuing with the remaining chapters (which include numerous additional characters and locations). There as also another complexity: in making the programme available to a selection of colleagues for testing, they invariable could not even get the hang of inputting simple prompts (e.g. read book), which was a requirement to even start playing the game. The game, or at least chapter one of the game, continues to lurk on the internet for anyone brave enough, but like the impossible pursuits of Bouvard and Pécuchet, it likely only drives one mad. Of course, ultimately the was meant to be the point. From the surviving notes of Flaubert (remembering he never actually completed the novel in his lifetime), we are led to understand the two characters descend into madness, living out their days idling copying any scraps of text that come their way. The idea of the online text adventure version was to lead the player up to this very point of ‘madness’ and then release them back out into the wilds of the Internet itself. Isn’t the Internet, ultimately, the ‘encyclopaedia as farce’ Flaubert always had in mind?

§

Two Cultures

There is a growing discourse, which cuts across numerous domains, concerned with Big Data, new technologies, artificial intelligence, new imaging techniques, augmented reality and the metaverse etc.. Yet, arguably, despite widespread media reports and a growing popular consciousness of these advances, it is perhaps the case that the current situation has only reignited the problem of ‘two cultures’ – as laid out by C.P. Snow in the 1960s, when he argued of a perennial gulf of misunderstanding between the sciences and the arts and humanities. While there is no shortage of causal and/or non-technical dialogues taking place, it is hard to find genuine sites of exchange and collaboration. Snow famously compared the importance of knowing the Second Law of Thermodynamics in the sciences to having read a work of Shakespeare in the humanities. Unless someone is able to converse ably between such ‘readings’ there would be no real basis for exchange. Indeed, Snow later believed the comparison could be made starker: ‘If I had asked an even simpler question’, he noted, ‘such as, What do you mean by mass, or acceleration […it would be] equivalent of saying, Can you read? – not more than one in ten of the highly educated would have felt I was speaking the same language’. (It was an argument that prompted a strong critique from F.R Leavis, yet the phrase ‘Two Cultures’ persists).

Today, despite a plethora of literatures and rhetoric concerning the ‘idea’ of inter-disciplinarity and even trans-disciplinarity, there remains a good deal of unevenness and ‘myth’. At best, it is perhaps the case that new fields of enquiry, such as ‘visual culture’, become a kind of interdiscipline (albeit still formulated within the particular domain, remaining on one side of the so-called Two Cultures divide. Alternatively, to borrow from W.J.T. Mitchell’s account of (and indeed delight over) ‘indiscipline’, forays into another disciplinary area often only affect ‘turbulence or incoherence at the inner and outer boundaries of disciplines’. Which is to suggest: ‘If a discipline is a way of ensuring the continuity of a set of collective practices (technical, social, professional, etc.), “indiscipline” is a moment of breakage or rupture when the continuity is broken and the practice comes into question’.

Yet, what would actual existing inter-disciplinarity look like? It would require the ability of different areas of research, different methods, different modalities, to not simply work together (which in reality can often result in a dominant partner, with interlocutors in the service of an already existing set of problematics), but also to formulate research questions and paradigms together. It would be to allow for a more reflective, deliberative, and dialogic ‘space’ to enhance and stimulate new research and advances in knowledge (see James Elkins’ Is Stories from the End of Representation). In part, this is what is espoused with the term ‘transdisciplinary’, yet still C.P. Snow’s simple test remains unnerving.

Speaking at a recent Turing Institute event, Kate Crawford closed by praising the growing diversity of those engaged in contemporary scholarship (not least in terms of gender). Yet, equally, she bemoaned the loss of a certain spirit of interdisciplinary dialogue, more evident, she argued, in the early part of the twentieth century, when, for example, anthropologists talked with computer scientists at public events. It was this observation that helped the Structuralism and AI project get started, and, indeed, it is an interdisciplinary approach that remains central to exploring new ‘units of analysis’ for AI.

See also: ‘The Art of Coding: A Cruel Optimism?‘