Project Mytheme

‘There is no reason why the simple shapes of stories can’t be fed into computers, they are beautiful shapes.’ – Kurt Vonnegut

‘There is very good reason why myth cannot simply be treated as language if its specific problems are to be solved; myth is language: to be known, myth has to be told; it is a part of human speech. In order to preserve its specificity we must be able to show that it is both the same thing as language, and also something different from it.’ – Lévi-Strauss, ‘The Structural Study of Myth’

‘How shall we proceed in order to identify and isolate these gross constituent units or mythemes? We know that they cannot be found among phonemes, morphemes, or semetmes, but only on a higher level; otherwise myth would be confused with any other kind of speech. Therefore, we should look for them on the sentence level.’ – Lévi-Strauss, ‘The Structural Study of Myth’

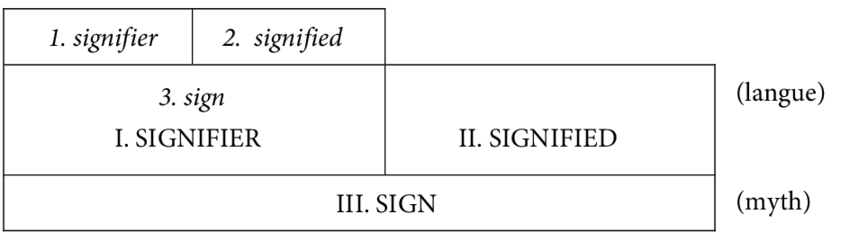

‘It can be seen that in myth there are two semiological systems, one which us staggered in relation to the other: a linguistic system … which I shall call the language-object, because it is the language which myth gets hold of in order to build its own system; and myth itself, which I shall call metalanguage, because it is a second language, in which one speaks about the first’. – Roland Barthes, ‘Myth Today’

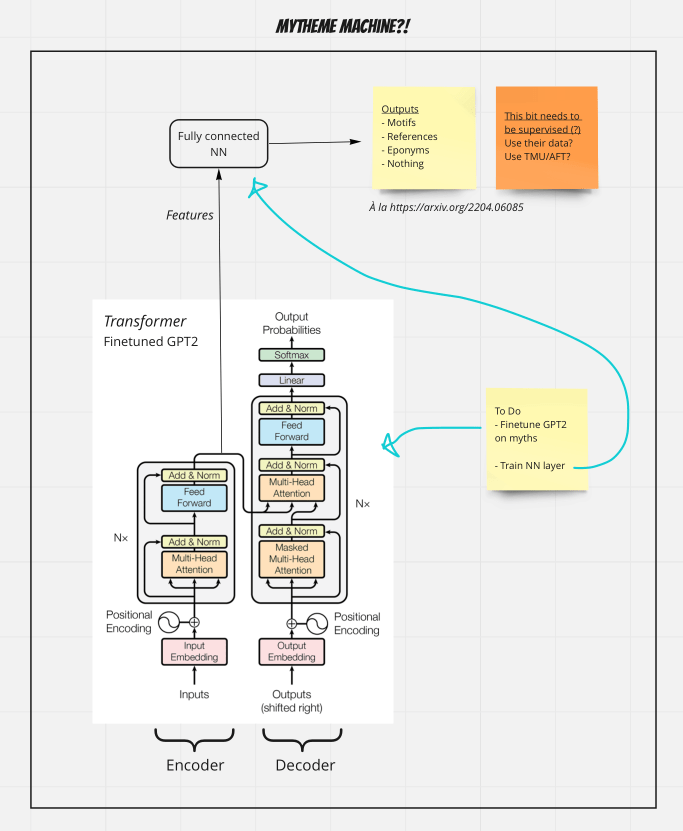

The notes collected on this site seek to underline a practical, interdisciplinary investigation, which in simple terms might be described as the building of a ‘mytheme machine’, or a second-order signification system. The purpose of which is to challenge and extend current capacities of AI approaches in language comprehension and text generation.

Unit of Meaning: Mytheme

The term mytheme is taken from the work of anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, the notable exponent of structuralism in the mid-twentieth century, who sought to show universal structures of thought. Echoing the term ‘phoneme’ (as the basic units of sound used in language), Lévi-Strauss coined the termed ‘mytheme’ to identify the basic units of meaning from vast collections of stories and myths from around the world. While myths vary widely (i.e. exhibiting variance in contents, elements and plot), it was possible to show the mythemes as persistent forms of invariance. During the development of his ideas (for anthropology), Lévi-Strauss held a keen interest in information theory and cybernetics, and also speculated on what might be achieved through the then emergent developments in computing.

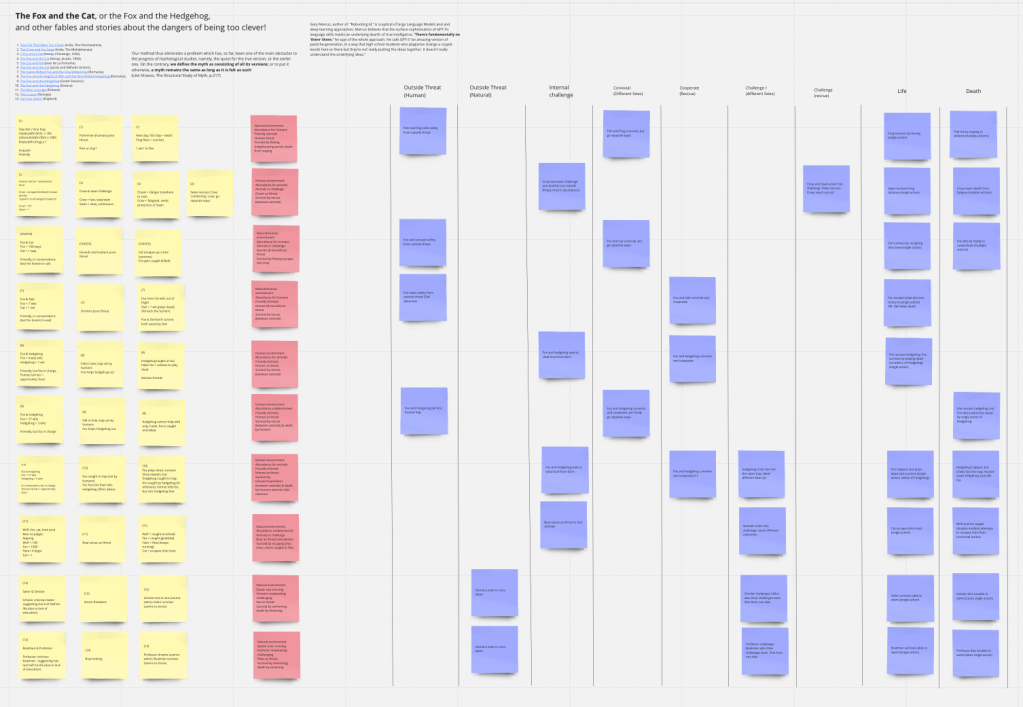

A key text for this project is Lévi-Strauss’ essay ‘The Structural Study of Myth’ (originally published in Journal of American Folklore, in 1955). It is here he offers the clearest definition of the mytheme (captured, for example, in the two quotes from Lévi-Strauss, as the top of this page). It is worth quoting at some length to lay out an understand of the mytheme as a ‘unit of meaning’ and what is at stake in seeking to analyse it:

In order to preserve its specificity we must be able to show that [myth] is both the same thing as language, and also something different from it. Here, too, the past experiences of linguists may help us. For language itself can be analyzed into things which are at the same time similar and yet different. This is precisely what is expressed in Saussure’s distinction between langue and parole, one being the structural side of language, the other the statistical aspect of it, langue belonging to a reversible time, parole, being non-reversible. If those two levels already exist in language, then a third one can conceivably be isolated.

We have distinguished langue and parole by the different time referents which they use. Keeping this in mind, we may notice that myth uses a third reference which combines the properties of the first two. On the one hand, a myth always refers to events alleged to have taken place long ago. But what gives the myth an operational value is that the specific pattern described is timeless; explains the present and the past as well as the future. This can be made clear through a comparison between myth and what appears to have largely replaced it in modern societies, namely, politics. When the historian refers to the French Revolution, it is always as a sequence of past happenings, a non-reversible series of events the remote consequences of which may still be felt at present. But to the French politician, as well as his followers, the French Revolution is both a sequence belonging to the past – as to the historian – and a timeless pattern which can be detected in the contemporary French social structure which provides a clue for its interpretation, a lead from which to infer future developments. […] It is that double structure, altogether historical and ahistorical, which explains how a myth, while pertaining to the realm of parole and calling for an explanation as such, as well as to that of langue in which it has expressed, can also be an absolute entity on a third level which, though it remains linguistic by nature, is nevertheless distinct from the other two. (Lévi-Strauss, ‘The Structural Study of Myth’, pp.209-210)

Based on this account of ‘myth’ (as a type of speech), Lévi-Strauss poses two working hypothesis:

(1) Myth, like the rest of language, is made up of constituent units. (2) These constituent units presuppose the constituent in present in language when analyzed on other levels – mainly, phonemes, morphemes, and sememes – but they, nevertheless, differ from the latter in the same way as the latter differ among themselves; they belong to a higher and more complex order. For this reason, which will call them gross constituent units. (pp.210-211)

Having identified a specific ‘unit of meaning’, Lévi-Strauss accepts the only way to proceed is ‘tentatively, by trial and error, using as a check the principles which serve as a basis for any kind of structural analysis: economy of explanation; unity of solution; and the ability to reconstruct the whole from a fragment, as well as later stages from previous ones’ (p.211). He explains his method as follows:

The technique which has been applied so far by this writer consists in analyzing each myth individually, breaking down its story into the shortest possible sentences, and writing a sentence on index card bearing a number corresponding to the unfolding of the story.

Practically each card with thus show that a certain function is, at a given time, linked to a given subject. Or, to put it otherwise, each gross constituent unit will consist of a relation.

However, the above definition remains highly unsatisfactory for two different reasons. First, it is well known to structural linguists that constituent units on all levels are made up of relations, and the true difference between our gross units and the others remains unexplained; second, we still find ourselves in the realm of a non-reversible time, since the numbers of the cards correspond to the unfolding of the narrative. Thus the specific character of mythological time, which is which as we have seen is both reversible and non-reversible, synchronic and diachronic, remains unaccounted for. From this brings a new hypothesis, which constitutes the very core of her argument: the true constituent units of a myth are not the isolated relations but bundles of such relations, and it is only as bundles that these relations can be put to use and combined so as to produce a meaning. Relations pertaining to the same bundles may appear diachronically at remote intervals, but when we have succeeded in grouping them together we have reorganized our myth according to a time referent of a new nature, corresponding to the prerequisite of the initial hypothesis, namely a two-dimensional time referent which is simultaneously diachronic and synchronic, and which accordingly integrates the characteristics of langue on the one hand, and those of parole on the other. To put it in even more linguistic terms, it is as though the phoneme were always made up of all its variants. (pp.211-212)

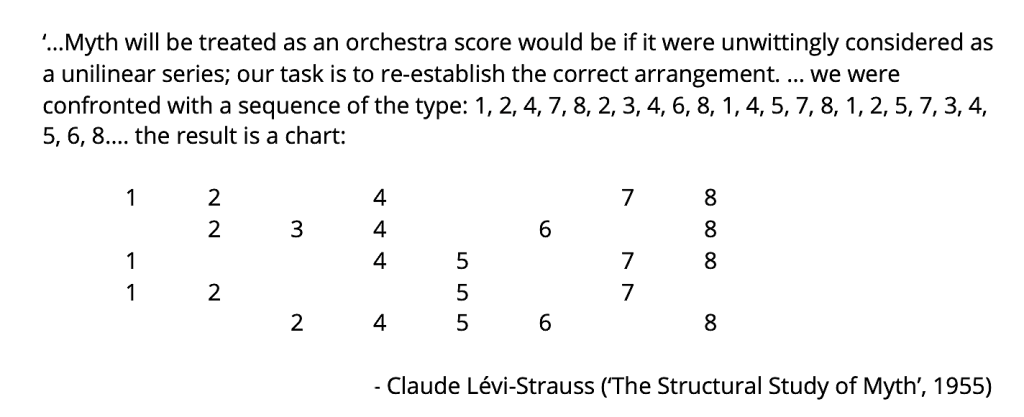

As has been the ‘motif’ of this project (shown on the opening page of this site), Lévi-Strauss goes onto compare his analysis of myths with a musical score, whereby we are not just looking at the diachronic unfolding of narrative, but also the synchronic selections. More importantly, the vertical axis is not the mere swapping in and out of alternatives, but, more akin to sedimentary rock, the various fault lines whereby invariances can be observed. He writes:

Multi-Dimensional

There is a key line in Lévi-Strauss’ essay, ‘The Structural Study of Myth’, that acts as the trigger for the whole undertaking of this project. In fact, I realise now, it is a line that has stayed with me (unconsciously for the most part) ever since reading it as an undergraduate. Having explained an elaborate procedure using ‘vertical boards about six feet long and four and a half feet high’ to lay out index cards, as a means to ‘build up three-dimensional models’ to plot a matrix of ‘structural’ components of myths and storytelling from around the world, Lévi-Strauss remarks:

…as soon as the frame of reference becomes multi-dimensional (which occurs at an early stage …) the board system has to be replaced by perforated cards, which in turn require IBM equipment, etc. (p.229)

Reference here to ‘IBM equipment’ is of course eponymous of the computer more generally. Yet, it was a ‘commodity’ unavailable for use at the time by a mere anthropologist. For me, today, the question remains, ‘what if…’, what might have happened had Lévi-Strauss had access to the vast computing power we now hold (not least in our mobile phones, let along standalone computers)? Addition to which, no less importantly, how might we consider his work today given the advances in multi-dimensional maths and the development of new hardware, in the form of altered virtual neural nets?

Structuralist anthropology (of which Lévi-Strauss is considered the pioneer) and structuralism more broadly (relating to linguistics, anthropology and critical theories from the 1950s – late 1970s) lost prominence and today is largely dismissed (unfairly I would argue). Philippe Descola explains as follows:

It so happens that, in one of those swings that are customary … the study of structural factors has for some time found itself particularly discredited. It is likened to an icy objectivism that irremediably dissolves all that goes to make up the richness and dynamism of social exchanges. Associated with it is the cliché of an interplay of timeless structures, hypostasized as essences that function in the manner of a series of actions executed by automata lacking any initiative of affects. Against this position (which no one ever held), the emphasis is now laid upon the creativity of the agency of social actors, upon the role played by historical contingency and resistance to hegemonies in the invention and cross-fertilization of cultural forms, upon the self-evident power and spontaneity of practice and the innocence now forever lost of all interpretative strategies. (Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, p. 91).

As Descola notes, within structuralist circles, ‘no one ever held’ the kinds of views that are today evoked to critique. Although the references to ‘icy objectivism’ and ‘a series of actions executed by automata lacking any initiative of affects’ might well described recent outputs of Large Language Models, the reason for many the phenomena of ChatGPT etc. can be unnerving. The contention here is that structuralism provides a pertinent way into examining both the recent ‘success’ of probabilistic based AI and how we might consider the greater complexities of meaning making.

Descola situates carefully between upholding a structuralist approach, while also being alert to creativity and the agency of social actors. His real interest is in widening the ‘palate’ of our descriptions (or rather perceived ontologies) of the world. There is important political import at stake in such work (which cannot be picked up here in detail). Descola’s project is neatly summed up when he writes:

Even if we recognize the contingency of the dualism of nature and culture and the difficulties that this introduces into any apprehension of nonmodern cosmologies, we should nevertheless not be led to neglect to seek for structural frameworks that can account for the coherence and regularity of diverse ways in which humans live and perceive their involvement in the world. However useful a physiology of interactions may be, it amounts to nothing without a morphology of practices, a praxeological analysis of forms of experience. To paraphrase a famous saying of Kant’s, structures without content are empty and experiences without forms are meaningless’ (Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, p.91).

Experimental Verification

One avenue of work is to consider Lévi-Strauss’ work in detail. Indeed, there is a body of literature that has sought to investigate his use of algebra and to consider the potential for complex computations of culture, yet his work has yet to be framed in terms recent developments in AI and machine learning. That said, Lévi-Strauss’ work cannot be used uncritically, nor can it simply be plugged directly into new computing methods. Rather, for the purposes of this project, it acts as an initial prompt and steer, with the actual methods needing to be led by contemporary mathematics and data science.

Nevertheless, the notion of ‘bundling’ relations sits at the core of the proposed work, as a means to question/extend how current natural language processing (NLP) might handle ‘second-order signification’, i.e. the specific contextual and coded use of language. Reference is made at the top of this page to Roland Barthes, citing from his famous essay ‘Myth Today’, which in (influenced by Lévi-Strauss) he sets out his well-known account of myth ‘as a type of speech’, and which he applies to the analysis of popular culture. The model adopts a first-order formulation of the sign as the first (and seemingly ‘naturalised’) component of a second-order signification. Of further note is Barthes’ essay, ‘Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives’, in which he argues narratives can be analyzed as a series of codes and conventions. He contends that narratives are not simply a linear sequence of events, but rather a complex interplay of language, symbols, and cultural norms. → For a summary, see On Narrative: An Interview with Roland Barthes; which is part of a section I edited for Theory, Culture & Society, ‘Notes on Structuralism‘.

To speculate: an incorporation of the aforementioned structuralist concerns into contemporary AI techniques is intended to pose advanced handling of ideological, aesthetic and contextual content. In effect, to render greater sense of ‘memory’ and coherence in NLP.

It is worth noting how ChatGPT has fine-tuned its underlying GPT-3.5/4 models with reinforcement learning in a process called reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). This uses human trainers to improve the model’s performance, with trainers playing both sides: the user and the AI assistant (see ethical note below). The reinforcement process ranks responses through a conversational approach. These rankings are used as ‘reward models’, which are then used to further fine-tune by several iterations of Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithms, which are proven to give stable results. The upshot is that as a chatbot version the LLM provides more sense of continuity to text entries from the user, giving more sense of ‘memory’ that aligns better with the ambitions of the project described here. It is notable that it is in this form, i.e. as ChatGPT, the language model has gained widespread interest and use. However, the functioning of the model is still very far from what is being suggested here in line with Lévi-Strauss’ account of mythemes (as gross constituent units).

Over the initial period of my Turing Fellowship and, more specifically, following pilot funds from the Web Science Institute of University of Southampton, some initial experimental work was conducted. Working in collaboration with Thomas Davies, the well-known Thompson Motif-Index (a catalogue used extensively in folklore studies) combined with the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index, was considered as a potential training dataset. Emulating Lévi-Strauss’ manual approach of laying out mytheme components on boards, the various iterations of the fable of the ‘Fox and Cat’ (and its variations) was tested. The fable tells of the dangers of being too clever (pertinent in exploring the domain of AI)! One of the dilemmas for this work is the heuristic nature of Lévi-Strauss’ method. The blue post-its shown below are an attempt to plot the various structural components of the story, to show (synchronic) commonalities and versioning, rather than be concerned with the (diachronic) unfolding of the stories. The difficulty of the task, achieved only manually (albeit brilliantly by Lévi-Strauss), underlies a critical problematic.

The pilot funds really only afforded the means to test the validity of the project’s underlying claims, i.e. the value of considering older structuralist considerations; and provided the (not unimportant) means to ground a properly interdisciplinary approach. An early model, devised and tested by Thomas Davies, relates to the following schematic (but the practical results were inconclusive):

Avenues of Enquiry

The frames of reference are broad, and ambitious. As such, it is worth saying that the proposed ‘machine’ is best understood on two levels: as both a software-based diagnostic tool and a wider conceptual project, or ambition. The work undertaken represents an interdisciplinary approach, with research problems, questions and testing worked through at each stage collaboratively. At its core, the mytheme machine bridges ideas, concepts and methods from structural linguistics and anthropology (and semiology), with computer and data science and mathematics.

Further Reading / Research

Toward an Atlas of Cultural Commonsense for Machine Reasoning (Anurag Acharya, Kartik Talamadupula, Mark A Finlayson)

DeepMet: A Reading Comprehension Paradigm for Token-level Metaphor Detection (Chuandong Su, Fumiyo Fukumoto, Xiaoxi Huang, Jiyi Li, Rongbo Wang and Zhiqun Chen)

Learning a Better Motif Index: Toward Automated Motif Extraction (W. Victor H. Yarlott et al.)

Finding Trolls Under Bridges: Preliminary Work on a Motif Detector (W. Victor H. Yarlott et al.)

Computational challenges to test and revitalize Claude Lévi-Strauss transformational methodology (Albert Doja, Laurent Capocchi, Jean-François Santucci)

Automatic Extraction of Narrative Structure from Long Form Text [thesis] (Joshua Daniel Eisenberg)

Machine learning: A structuralist discipline? (Christophe Bruchansky)

Meaning without reference in large language models (Steven T. Piantadosi, Felix Hill)

Proceedings of the Workshop on Figurative Language Processing (2018)

Structuralism, computation and cognition: The contribution of glossematics (David Piotrowski)

Learning from data with structured missingness (Robin Mitra et al.)

Attention is All You Need (Ashish Vaswani et al.)

Improving Productivity in Hollywood with data science: using emotional arcs of movies to drive product and service innovation in entertainment (Marco Del Vecchio, Alexander Kharlamov, Glenn Parry, Gonna Pogrebna)

The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes (Andrew J Reagan et al.)

Ethical Note

It is important to point out: for the development of the safety system used in ChatGPT against toxic content (e.g. sexual abuse, violence, racism, sexism, etc.), OpenAI used outsourced Kenyan workers earning less than $2 per hour. These workers were exposed to toxic and dangerous conten, leading to some describing the experience as “torture” (see Time Magazine).