Ut pictura poesis: Phoneme/Pixel

In short, many poetic features belong not only to the science of language but to the whole theory of signs, that is, to general semiotics. This statement, however, is valid not only for verbal art but also for all varieties of language since language shares many properties with some other systems of signs or even with all of them (pansemiotic features).

Roman Jakobson, ‘Linguistics and Poetics’, 1966, p.351

In what follows, two ‘exhibits’ are offered as prompts ahead of the reading group session on material by Roman Jakobson. Counterintuitively perhaps, the exhibits turn attention to the visual rather than the verbal (as readily associated with Jakobson). Yet, in doing so the relationship between word and image is significant, not least as AI technologies continue to draw primarily on language-based databases and categories (see chapters 3 & 4, Crawford, 2021). Of course, the relationship the word/image nexus remains one of the most complex and enduring conundrums (see Chapter 3, ‘Image and Text’, Manghani, 2013, pp.59-87). As W.J.T Mitchell (2003) notes, ‘the causal remark of the Roman poet Horace “ut pictura poesis” (as is painting, so is poetry) became the foundation for one of the most enduring traditions in Western painting and has served as a touchstone for comparisons of the “sister arts” of word and image ever since’. Lessing’s Laocoon of 1766, suggests painting and poetry ‘should be like two just and friendly neighbors’, and yet the text was written to uphold the importance of literary work. While Greenberg’s modernism of the early twentieth century argued for the distinctness and difference of verbal and visual media, notably privileging the opticality of painting. And yet, equally, beyond the various divides in learned debates, wider cultural trends haven frequently been ‘dominated by the aesthetics of kitsch, which freely mixes and adulterates the media’ (Mitchell, 2003).

In Picture Theory, Mitchell (1994, p.89n) provides a brief note on three different typographic conventions that can be employed to designate different relations of text and image. We can write ‘image/text’, with a slash, to denote ‘a problematic gap, cleavage, or rupture in representation’. The agglutination of ‘imagetext’ can be used to describe ‘composite works (or concepts) that combine image and text’, and, the use of a hyphen, as in ‘image-text’, ‘designates relations of the visual and verbal’. These are useful conventions, delineating three different ways of thinking about text and image, but in themselves they are not necessarily easy to apply. For example, how should we describe Milton’s evocative phrase ‘in their looks divine’? It is clearly text, yet equally it conjures an image as well as comments on the visual. As an eloquent line of poetry we might not associate it with a ‘rupture in representation’. Yet, as Mitchell (1987, p.35) suggests, this line ‘deliberately confuses the visual, pictorial sense of the image with an invisible, spiritual, and verbal understanding’. Ostensibly, it would be possible to label the phrase with any one or all three of these different conventions, image/text, imagetext and image-text.

At a more philosophical level, then, it is difficult to mark the borderlines between words and images. We might consider the well-known illusion of the duck-rabbit to be purely a matter of image, or rather two images. Yet, as we know from Wittgenstein’s (1953) treatment, our ability to identify what we see through language is what enables us to see both images (duck, rabbit, and the oscillation between): ‘Being able to see both the duck and the rabbit, to see them shift back and forth, is possible only for a creature that is able to coordinate pictures and words, visual experience and language’ (Mitchell, 2003). Wittgenstein referred to this phenomenon as ‘aspect perception’, or our ability to ‘see as’ something. We can see an object based on the sheer physical properties of vision, but we can also notice an aspect. E.g. ‘To the untrained eye, a blueprint schematic might be mere geometric, maze-like squiggles. But to an engineer, it is “seen as” a blueprint. The engineer notices an aspect that others do not’ (Thomson, 2022). It is precisely aspect blindness that besets our use of computer vision (more of which below).

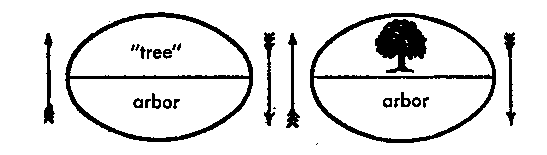

Mitchell also reminds us of the largely neglected ‘image’ in Ferdinand de Saussure’s well-known diagram setting out the arbitrary nature of the sign, with regards structural linguistics:

The picture of the tree in this diagram is consistently ‘overlooked’ (in every sense of this word). It is taken to be a mere place-holder or token for an ideal entity, its pictoriality a merely accidental or conveniently illustrative feature. But the rendering of the signified concept as picture or what Saussure calls a ‘symbol’ constitutes a fundamental erosion in the Saussurean claim that ‘the linguistic sign is arbitrary’ … (that is, the linguistic sign is ‘empty,’ ‘unmotivated,’ and without any ‘natural bond’ between signifier and signified). The problem is that an important part of the sign seems not to be arbitrary. As Saussure notes, the pictorial tree, the ‘symbol’ that plays the role of signified concept, ‘is never wholly arbitrary; it is not empty, for there is the rudiment of a natural bond between the signifier and signified’ …The word/image difference, in short, is not merely the name of a boundary between disciplines or media or kinds of art: it is a borderline that is internal to both language and visual representation, a space or gap that opens up even within the microstructure of the linguistic sign and that could be shown to emerge as well in the microstructure of the graphic mark.

Mitchell, ‘Word and Image’, 2003

As will emerge by the close of this entry, in reference to Open AI’s DALL-E 2, an AI system that creates realistic images from natural language inputs, we can begin to question not only the phoneme as the basic building blocks of meaning, but also the pixel. First, however, we begin with the problematic of ‘poetic function’ for AI…

Exhibit A: ‘Wile E. Coyote Stuff’

Following a somewhat flimsy presentation on production plans for a Tesla AI humanoid robot (designed to perform general chores for humans), Elon Musk and a group of his fellow engineers field comments from a nonetheless informed audience. They ask a range of practical and technical questions. And while the presentation had focused on the ambitious unveiling of a fully-functioning robot (to be ready by 2023), the point is made that the Tesla self-driving car is essentially already a robot (on wheels) and that the same camera-based AI technology will be fitted to a humanoid form. Inevitably, most of the questions gravitate back to the efficacies, ethics and future of the already existing car. One member of the audience raises the question of adversarial tactics, whereby someone might use 2D images to trick the car into thinking something is up ahead when in fact it is not (the video-clip and transcript are given below). Musk replies first with an analogy to the well-known Road Runner cartoon, in which hapless Wile E. Coyote invents all sorts of elaborate, but ultimately ineffective, contraptions and subterfuge to catch the Road Runner. Putting aside the hubris typically associated with Elon Musk, the exchange is revealing, not only of the deficiencies of computer-aided perception (as opposed to recognition), but also the role of language in navigating the problem.

Audience Member: Are you worried at all, since you don’t have any depth sensors on the car, that people might try adversarial attacks, like printed out photos or something to try to trick the RGB neural network [as used for AI-powered image classification]? (see: notes on image processing via a ‘Convolution Neural Network‘)

Elon Musk: Yeah, like what, pull something like Wile E. Coyote stuff? You know, like paint the tunnel on the… on the wall? It’s like: oops! [laughter] Erm… We haven’t really seen much of that, erm… I mean … for sure, like right now if you, most likely, if you have like a t-shirt with a … with like a stop sign on it (which I actually have a t-shirt with a stop sign on it), and then you, like, flash the car [demonstrates opening his jacket to flash his t-shirt]. It will… it will stop [laughter]. I’ve proved that … erm, but we can obviously, as we see these adversarial attacks, then we can train the cars to er… you know, notice that ‘well it’s actually a person wearing a t-shirt with a stop sign on it, so it is probably not a real stop sign’…

First of all, we have the simple problem: computers don’t know the difference between ‘things’ and images of things. Although perhaps, in time, this can be resolved by fixing the math, adjusting the algorithm (e.g., see Jhamtani, et al., 2021). Yet, according to Musk’s strategy, we first need to ‘see’ the problem to then devise a workaround; so potentially only a ‘whack-a-mole’ approach, or again Wile E. Coyote type ‘stuff’! Secondly, however, and perhaps more significantly, the ability to think this problem through takes us back to language.

It is useful to reference Roman Jakobson and Morris Halle’s Fundamentals of Language, and in particular Part 2, on two aspects of language (in reference to two types of aphasia). Jakobson and Halle remind (in reference to Carnap’s Means and Necessity, 1947) of our ability in language to speak about things and of them, so shifting from ‘object language’ and ‘metalanguage’. Thus, ‘we may speak of English (as metalanguage) about English (as object language) and interpret English words and sentences by means of English synonyms, circumlocutions and paraphrases’ (p.67). Furthermore, they observe how our use of metalanguage often leads interlocutors to check whether one another are speaking of the same thing (using the same ‘code’):

‘Do you follow? Do you see what I mean?’, the speaker asks, or the listener himself breaks in with ‘What do you mean?’ Then, by replacing the questionable sign with another sign from the same linguistic code, or with a whole group of code signs, the sender of the message seeks to make it more accessible to the decoder. (p.67)

We see this in the brief exchange between the audience member and Elon Musk, with the latter checking rhetorically if the question refers to something like ‘Wile E. Coyote stuff’. In this case, metaphor (or similarity) is used to both affirm the code being spoken of, and to offer something more accessible (so to decode). Also, further, the anecdote of the t-shirt with a stop sign reveals a deficiency in how current models of computer vision operate. We might suggest this a form of visual agnosia (the impairment in recognizing visually presented objects). But, again, the framing of language is pertinent. Jakobson and Halle draw upon the case of aphasia, which typically manifests in one of two ways, either as the difficulty to comprehend or to formulate language, for which they set out the underlying deficiency as either one of ‘selection and substitution, with relative stability of combination and contexture; or conversely, in combination and contexture, with relative retention of normal selection and substitution’ (p.63). In the first case, the patient can still apply contextual understanding, so can complete phrases and connect words, yet find it difficult to initiate speech (to select words); ‘the more a word is dependent on the other words of the same sentence and the more it refers to the syntactical context, the less it is affected by the speech disturbance’ (p.64). In the second case, impairment is of ‘the ability to propositionize, or generally speaking, to combine simpler linguistic entities into more complex units […] This contexture-deficient aphasia, which could be termed contiguity disorder, diminishes the extent and variety of sentences. The syntactical rules organizing words into a higher unit are lost; this loss, called agrammatism, causes the degeneration of the sentence into a mere “word heap”’ (p.71).

While recognising aphasia presents in numerous and diverse ways, Jakobson and Halle nonetheless summarise their account by reference to the difference between metaphor (similarity disorder) or metonymy (continuity disorder) (pp.76-82). And which they map between the poles of poetry and prose, respectively:

In poetry there are various motives which determine the choice between … alternants. The primacy of the metaphoric process in the literary schools of romanticism and symbolism has been repeatedly acknowledged, but it is still insufficiently realized that it is the predominance of metonymy which underlies and actually predetermines the so-called ‘realistic’ trend […] Following the path of contiguous relationships, the realistic author metonymically digresses from the plot to the atmosphere and from the characters to the setting in space and time. He [sic] is fond of synecdochic details. In the scene of Anna Karenina’s suicide Tolstoj’s [sic] artistic attention is focused on the heroine’s handbag; and in War and Peace the synecdoches ‘hair on the upper lip’ or ‘bare shoulders’ are used by the same writer to stand for the female characters to whom these features belong. (p.77-78)

Returning to the words of Elon Musk, we get a combination of metaphor and metonymy. We start with the metaphoric connection to Wile E. Coyote, which is then metonymically developed through the reference to painting a tunnel on a wall. This forms the subtle bridge with the problem of the Tesla car (indeed, we might imagine a car driving through a tunnel in a glossy car advertisement). Unlike the Road Runner, however, the car can be fooled by a trompe-l’œil effect. The example of the t-shirt oscillates too. The stop sign is purely symbolic (metaphor), yet for the car, it might be part of the landscape (contiguous, metonymy). We can speculate whether it is easier to train AI to relate to metaphors, more readily than metonymy.

In addition, there is a way of reading Musk’s final remarks as if he is speaking the part of an AI neural network itself. In the transcript I have included the use of speech marks to indicate this idea (you can listen to the audio on the video to see if you agree): ‘it’s actually a person wearing a t-shirt with a stop sign on it, so it is probably not a real stop sign’. The suggestion is that this line is the thought-pattern necessary to the AI; necessary to how we might end up needing to code the AI, so as to make up its own mind: metaphor or metonymy? The line demonstrates what Jakobson (1966) refers to as the ‘poetic function’; which, he writes, ‘by promoting the palpability of signs, deepens the fundamental dichotomy of signs and objects’ (p.356). In short, there is a fluidity to this line that performs the very fluidity of thought required to reach its conclusion.

One further level of language to consider (again, demonstrating the poetic, phatic function) is Musk’s own speech patterns, which I have tried to replicate faithfully, if only as a reminder of how the codes and conventions of metalanguage can err, and yet still readily communicate. In this case, despite the breaks and elisions Musk nonetheless manages to ‘entertain’ the crowd and sets out his response with reasonable clarity. Yet, it is hard to consider current AI managing to navigate Musk’s ‘poetry’, which as metalanguage begins with a very specific popular culture reference, introduces both verbally and visually (through the gesture of opening his coat) a secondary image, and all delivered through the ‘stops and starts’ of his own thought patterns. In this case, language would certainly seem to get the better of (computer) vision. NB. See Toews (2022) on the ‘AI-complete’ problem, referring to the challenge to create AI that can understand language or see the way a human can.

Exhibit B: DALL-E 2

Perhaps the tables are turned with this second exhibit (or maybe we just go further down the rabbit hole of the image-text!). Circulating in the popular press, there have been numerous syndicated reports of Open AI’s updated DALL-E 2, which the company describes as ‘a new AI system that can create realistic images and art from a description in natural language’.

The software can combine concepts, attributes and styles; and as a particular enhancement of the original version, it not only can create new imagery, it can edit existing images (again simply through natural language commands). The ability to edit, referred to as ‘inpainting’, offers ‘realistic edits to existing images from a natural language caption. It can add and remove elements while taking shadows, reflections, and textures into account’ (see promotional video below).

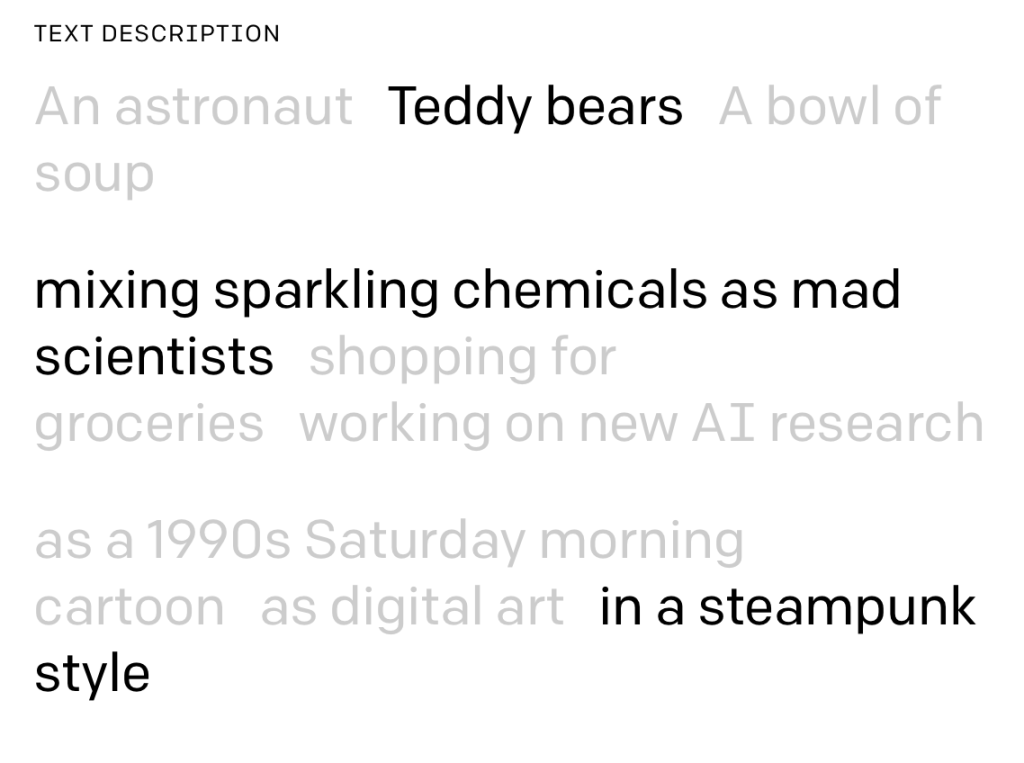

Various examples are provided online via an interactive menu of keywords. Two, slightly wild looking teddy bears (shown below) are the result of selecting the following text:

For further explanation see Open AI’s promotional video:

Interestingly, DALL-E 2 is currently labelled a ‘research project’ and is not publicly available. ‘As part of our effort to develop and deploy AI responsibly,’ explain Open AI, ‘we are studying DALL-E’s limitations and capabilities with a select group of users’. Noted safety mitigations include: preventing harmful generations, curbing misuse, and phased deployment based on learning. (The latter only describes the declared tactic to avoid unforeseen affordances, while the other two are seemingly the generic concerns anyone might have, without really knowing what exactly might go wrong!). The rhetoric of Open AI is inevitably about the benefits of AI: ‘Our hope is that DALL-E 2 will empower people to express themselves creatively’. Added to which, there is the suggestion of a form of metalanguage or meta-coding: ‘DALL-E 2 also helps us understand how advanced AI systems see and understand our world, which is critical to our mission of creating AI that benefits humanity’.

From a technical point of view, DALL-E 2 appears highly proficient. Building on the first iteration, the update boasts higher resolution, greater comprehension and faster rendering. Its ability to reinterpret and edit (inpaint) existing images is also significant. If anyone has tried creating a montage with Photoshop, and assuming you’ve got passed the basics of cutting and layering elements, it is still a painstaking task (fraught with problems and errors). Yet, with DALL-E 2, at pixel level, all number of seemingly seamless combinations of elements materialise through natural language prompts alone. Open AI suggest DALL-E 2 ‘has learned the relationship between images and the text used to describe them. It uses a process called “diffusion,” which starts with a pattern of random dots and gradually alters that pattern towards an image when it recognizes specific aspects of that image’. It is easy to be seduced by pseudo-terms such as ‘diffusion’. At present, it is likely the system ‘looks’ more proficient than it really is (as one 80s pop song put it, we need to ‘learn to ignore what the photographer saw’). The company admit they have focused on improving, rather than expanding the programme – i.e. within its ‘black box’ there are perhaps less combinations of images than we might imagine.

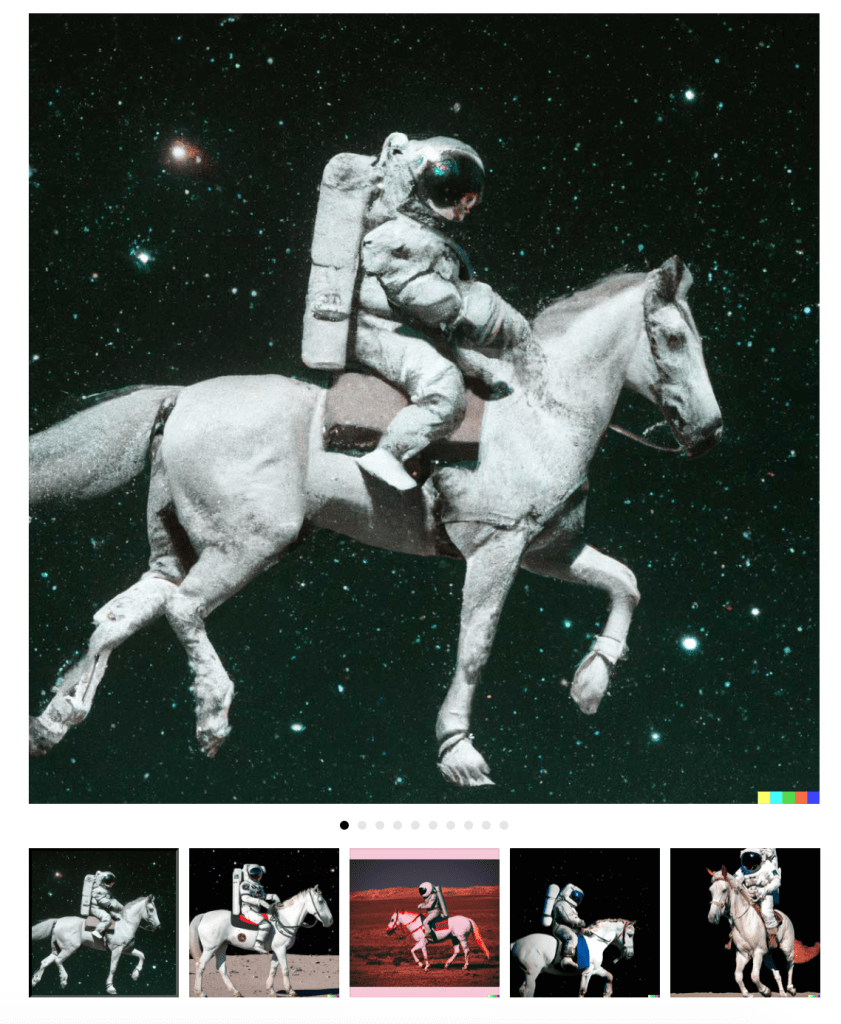

As Thomas Macaulay, for TNW, explains ‘DALL-E 2 is trained on pairs of images and their corresponding captions, which taught the model about the relationships between pictures and words’. He adds that some of its creations ‘look almost too good to be true. Yet the researchers say the system tends to generate visually coherent images for most captions that people try’. One example given by the company is of an astronaut, which is based upon a set of 9 images, or ‘models’. In the following image you can see the output based on the text descriptions: ‘An astronaut, riding a horse, in a photorealistic style’; and beneath you can see 5 of the 9 models it is derived from.

This example begins to show how the system works. And as one of the researchers at Open AI explains: ‘Sometimes, it can be helpful to iterate with the model in a feedback loop by modifying the prompt based on its interpretation of the previous one or by trying a different style like ‘an oil painting,’ ‘digital art,’ ‘a photo,’ ‘an emoji,’ etcetera. This can be helpful for achieving a desired style or aesthetic’(Prafulla Dhariwal cited in Macaulay, for TNW). It is tempting to suggest DALL-E 2 is currently more proof-of-concept than full product (at least in terms of scaling and general operability). Nonetheless, it is impressive, albeit, for all its impressiveness, we will also know ‘DALL-E 2 inherits various biases from its training data — and its outputs sometimes reinforce societal stereotypes’ (Macaulay, 2022; see also Crawford, 2021). In this respect, the same logic applies as Li (2017, p.8) explains for Google’s earlier development of predictive text: ‘Regardless of their stated goal as a mere aid for information retrieval, the statistically-rendered predictions are thus taken to be information as such. Put another way, this system designed for data storage, retrieval, and transmission is considered to be capable of generating new information’. The further point is that, here, we are invited ever more explicitly into the generation of new information, and not just that, but new information not merely at the level of phonemes and sentences, but at the level of the pixel (see #5 Shannon: Paper into Pixels) and hence all the myriad dots they join up…

References

Kate Crawford (2021) Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Roman Jakobson and Morris Halle (1956) Fundamentals of Language, Part II, ‘Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbance’, The Hague/Paris: Mouton, pp. 55-82.

Roman Jakobson (1966 [1960]) ‘Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics’, in Thomas Sebook (ed.) Style in Language (Proceedings of the Conference on Style, held at Indiana University, 1958). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, pp. 350-377.

Harsh Jhamtani, et al. (2021) ‘Investigating Robustness of Dialog Models to Popular Figurative Language Constructs’, Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 7476–7485, November 7–11, 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Thomas Macaulay (2022) ‘OpenAI’s new image generator sparks both excitement and fear’, Neural: AI and Futurism, TNW, 8 April, 2022.

Sunil Manghani (2013) Image Studies: Theory and Practice. Routledge.

W.J.T. Mitchell (1987) Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

W.J.T. Mitchell (1994) Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

W.J.T. Mitchell (2003), ‘Word and Image’, in Critical Terms for Art History. [Available online]

Jonny Thomson (2022) ‘Can a duck ever be a rabbit? Wittgenstein and the philosophy of “aspect perception”’, Big Think, 24 January, 2022.

Rob Toews (2022) ‘Language Is The Next Great Frontier In AI‘, Forbes, 13 February 2022.

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953) Philosophical Investigations, trans. by G. E. M. Anscombe. New York: Macmillan.