Experimental Verification

…we should not only be able to provide a more precise and rigorous formulation of the genetic law of the myth, but we would find ourselves in the much desired position of developing side by side the anthropological and the psychological aspects of the theory; we might also take it to the laboratory and subject it to experimental verification.

Lévi-Strauss, ‘The Structural Study of Myth’ (1955, emphasis added)

Premable

In Criticism and Truth, originally published in 1966 (in French), Roland Barthes responds to the fierce criticism he had received from the ‘old guard’ Sorbonne Professor of French Literature, Raymond Picard. Labelled as ‘new criticism’, Picard took aim at the work of a broad group of scholars (notably including Barthes), which he described as confused, obscurantist and, worst of all, disrespectful to literary tradition. Barthes’ retort, labelling in return Picard’s approach as ‘l’ancienne critique’, explained that what ‘old criticism’ cannot abide ‘is that “new criticism” concerns itself not with critical evaluation (the foundation of traditional forms of criticism) but with language itself’ (Allen, Roland Barthes, 2003, p.55). Here is not the place to enter into this debate, but importantly, Barthes’ underlying interest is to uphold the structuralist approach as scientific, referring to a ‘hypothetical model of description’. As Graham Allen notes: ‘The clearest example of this approach concerns a project to which Barthes was a major contributor, centred as it was within the [École Prâtique des Hautes Études], which attempted to lay the foundations for a structuralist analysis of narratives. Barthes’ “Introduction to the Structuralist Analysis of Narratives” … is his now classic contribution to that project’ (p.55-56). (This text of Barthes will be the focus of the third reading group session)

Today, the overtly scientific aims and methods of structuralism (at least regards literature) are easily forgotten, or perhaps more often used to deride the overall ‘enterprise’. The rise of ‘poststructuralism’ (of which Barthes was a key proponent) worked to unseat structuralism from within, turning increasingly away from language per se to the more expansive term of the ‘Text’, and pivoting from objective to subjective readings and forms of dissemination. The purposes of the current project, however, is to return to the earlier interests of structuralism. This is not intended to be at the expense of poststructuralism, which has been key to to the decentring of critical debates and positionalities. However, in the context of AI and Big Data, the idea is to look again at how structuralism was looking at the world, and what import it might still have (had its currency not waned).

One of the problems of contemporary methods (in machine learning, pattern recognition etc) is seemingly a lack of contextualisation. Machines are increasingly adept at identifying ‘information’, but without awareness of any value or wider relational significance. This is something that is considered below in comparing Claude Lévi-Strauss’ structuralist ‘algebra’ and contemporary algorithmic methods (notably non-negative matrix factorization).

It is worth saying, even within structuralism there were numerous debates and differences (François Dosse, for example, in his History of Structuralism, identifies differences and shifts from scientific to semiological to historical/epistemic structuralisms). Relations between Barthes and Lévi-Strauss were ‘complicated’. Letter exchanges between the two (Barthes, 2018, p.164-170), while incomplete, reveal a careful reading of one another’s work, as well as a referential tone from Barthes (the younger of the two). Indeed, Barthes would end up indebted to Lévi-Strauss for his endorsement of Barthes’ election to the Collège de France. Yet, in his letters, Lévi-Strauss is frequently strict, and teacherly in tone. In reading Criticism and Truth, he urges Barthes to be more radical, to look to the ‘inherently and objectively determinable forms’, rather than be drawn into what he describes as an ‘indulgence for subjectivity’. Against the ‘open text’ (which becomes so key to poststructuralism), he writes:

For me, the work is not open (a conception that opens it to the worst philosophy: that of metaphysical desire, of the subject justly denied, but in order to hypostatize its metaphor, etc.); it is closed, and it is precisely that closure that allows an objective study to be done on it. In other words, I do not distinguish the work from its intelligibility; structural analysis consists, on the contrary, of turning intelligibility in on the work.

Lévis-Strauss, 1963, p.166.

*

Algebraic Method

Doja, 2008, p.330.

Lévi-Strauss’s analysis of myth is operational to the extent that myth is seen as a working model of specific processes of human thinking. His presentation of the Mythologiques sequence is a kind of extended experiment, whose ‘laboratory’ is the geographical zone covered by the two Americas, the ultimate goal of the experiment being to uncover the inner logic of the human mind.

As already set out in #3 Myth and Meaning, Lévi-Strauss characterises structuralism as the search for invariance (as, for example, with his notational approach to reading myths from across the world), which in turn, as Albert Doja (2008) notes, underpins Lévi-Strauss ongoing consideration of how the mind works. The pertinence (or at least potential) in re-reading Lévi-Strauss today, vis-à-vis AI, centres around two things: firstly, Lévi- Strauss equates myth with a ‘working model’ of certain processes of human thinking; and secondly, he employs (or at least begins to set out) an algebraic method:

He attempted to demonstrate a logico-mathematical structure of mind and cognition by maintaining that myths and kinship systems exhibit a kind of algebraic structure. His finding of a kinship ‘algebra’ in his Elementary Structures of Kinship (1967 [1949]), which was provided with an imprimatur by renowned algebraist André Weil, seems widely accepted. By systematically using his method of structural analysis of myths, Lévi-Strauss maintained that it should be possible to organize all the known variants of a myth into a series of transformations resulting in a group of myths of the same logical type, the ‘set forming a kind of permutation group’ (Lévi-Strauss, […]). He also recognized the cognitive significance of analogical reasoning, in so far as the ‘savage mind’ can be defined as ‘analogical thought’.

Doja, 2008, p.329.

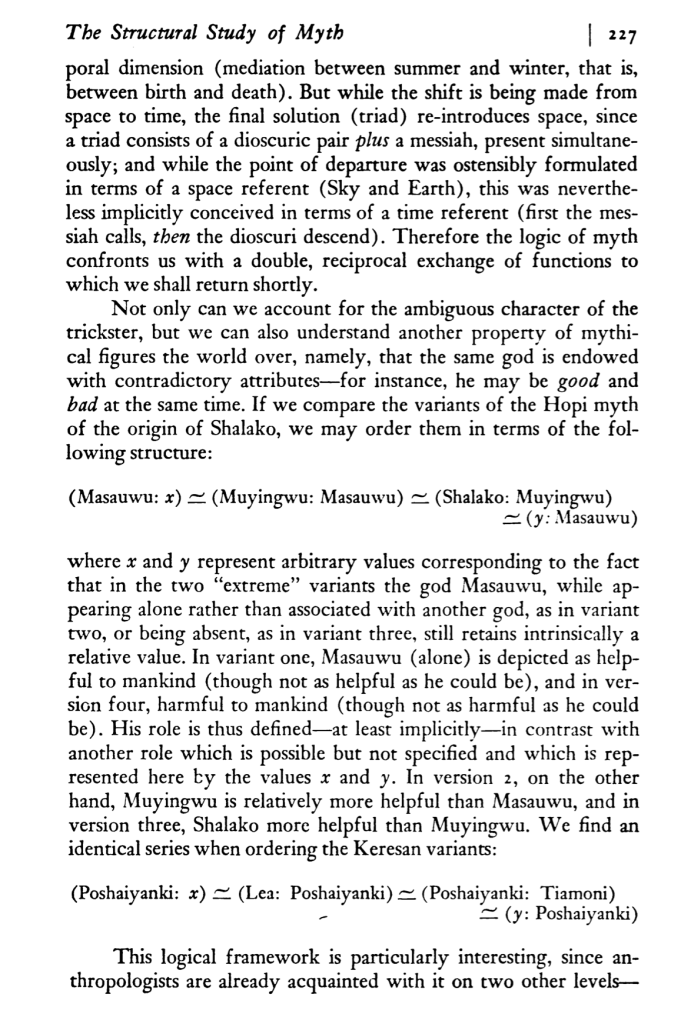

In note #3, I drew mainly upon Lévi-Strauss’ later reflections and synopsis of his structuralist method, from his lectures, Myth and Meaning. Here, however, it is worth focusing on the essay, ‘The Structural Study of Myth’, originally published in 1955. Towards the end of this essay, he offers what seems an astonishingly compressed ‘formula’ for the complex study of myth. Having studied thousands from around the world (and with the essay setting out an underlying, general structural method), he declares:

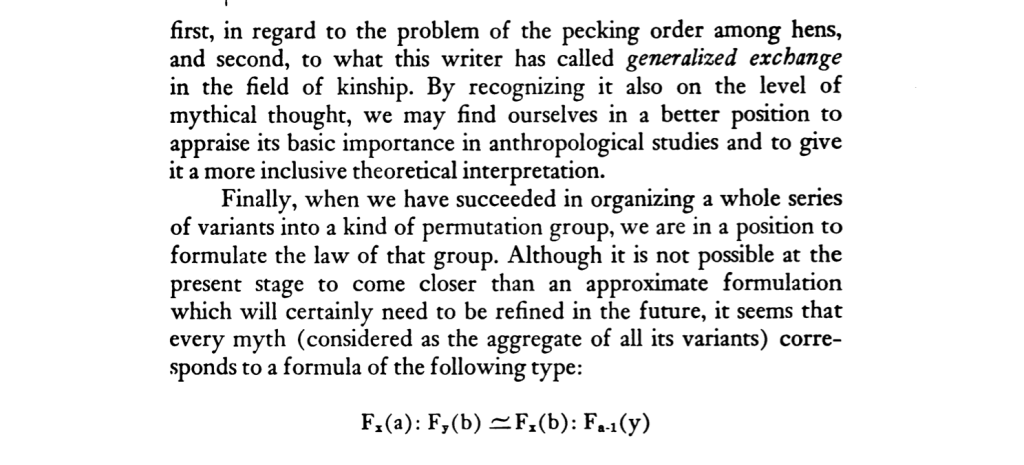

Finally, when we have succeeded in organizing a whole series of variants into a kind of permutation group, we are in a position to formulate the law of that group. Although it is not possible at the present stage to come closer than an approximate formulation which will certainly need to be refined in the future, it seems that every myth (considered as the aggregate of all its variants) corresponds to a formula of the following type:

Fx(a): Fy(b) ≃ Fx(b): Fa-1(y)

Lévi-Strauss, 1963, p.228.

Claude Lévi-Strauss refers to this as a ‘Canonical Formula’ for the structural analysis of myth, but which, as Pierre Maranda (2001, p.4) suggests, ‘looks somewhat cryptic to most scholars – mathematicians, social scientists, and humanists alike’. For more sustained enquiry into its application and where it is analysed and tested, see Maranda’s edited volume The Double Twist: From Ethnography to Morphodynamics (2001). For the purposes here, it is useful to note the constraints Lévi-Strauss felt at the time (bearing in mind he is writing in the mid-fifties), but equally of the future trajectory:

At this points it seems unfortunate that with the limited means at the disposal of French anthropological research no further advance can be made. It should be emphasised that the task of analysing mythological literatures, which is extremely bulky, and of breaking down into its constituent units, requires team work and technical help. A variant of average length requires several hundred cards to be properly analysed. To discover a suitable pattern of rows and columns for those cards, special devices are needed, consisting of vertical boards about six feet long and four and a half feet high, where cards can be pigeon-holed and moved at will. In order to build up three-dimensional models enabling one to compare the variants, several such boards are necessary, and this in turn requires a spacious workshop, a commodity particularly unavailable in Western Europe nowadays. Furthermore, as soon as the frame of reference becomes multi-dimensional (which occurs at an early stage, as has been shown above) the board system has to be replaced by perforated cards, which in turn require IBM equipment, etc.

Lévi-Strauss, 1963, p.228-229

In the quote from Lévi-Strauss’ at the very start of this note there is mention of taking the work ‘to the laboratory’, to ‘subject it to experimental verification’. In this case he is interested in the intersection with psychology, and in fact psychoanalysis (the quote comes from a paragraph on Freud’s reading of trauma, which is ‘structured’ in a specific way, and which elsewhere Lévi-Strauss connects by analogy to the structure or layering of rock in geology). For the purpose here, I will bracket out Lévi-Strauss’ interest in psychoanalysis, but reference to the unconscious is critical to his thinking and framing of structuralism (a future topic might well be on the prospects of unconscious thought patterns, as much as the sought after ‘consciousness’ of artificial general intelligence). Nonetheless, today, the ‘laboratory’ we might readily turn is the computer lab (as befits Lévi-Strauss’ thoughts on converting his system to ‘IBM equipment’), or more broadly to the domain of mathematics. Equally, we might consider the combined ‘laboratory’ of computer science and neuroscience (more on this below).

Before considering the contemporary significance of Lévi-Strauss work, it is useful to remind of the method as set out in ‘The Structural Study of Myth’, and in fact, for the purposes here, simply to ‘look’ at the method as it appears across the pages of the essay. (A visual account helps to consider the connections to contemporary machine learning, shown further below).

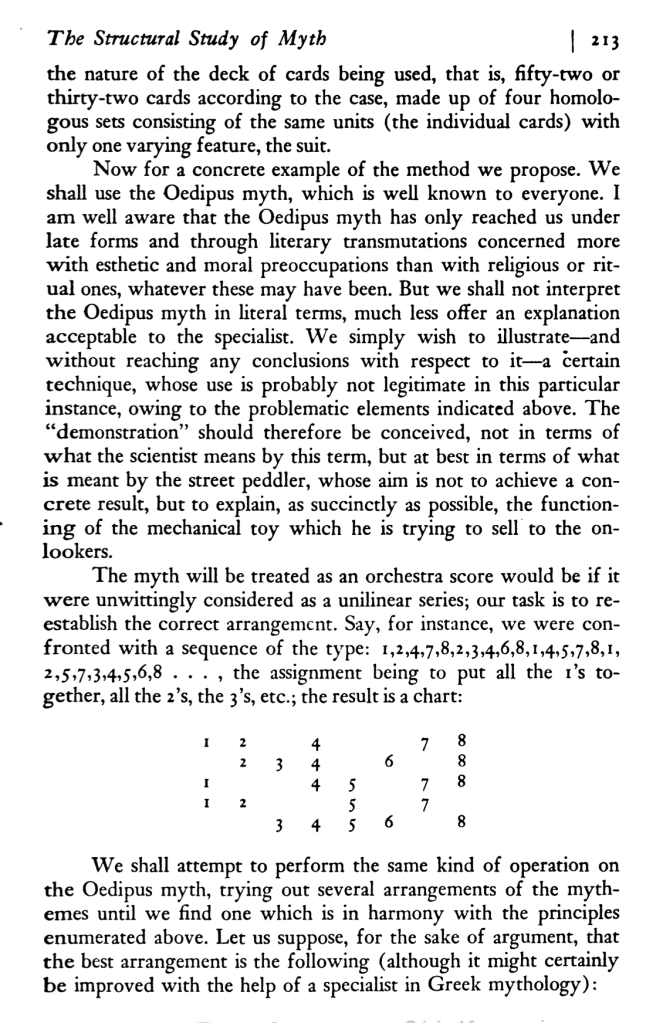

As described in #3 Myth and Meaning, Lévi-Strauss compares his analysis of myths (of stories) with a musical score, whereby we are not just looking at the diachronic unfolding of narrative, but also the synchronic selections. More importantly, the vertical axis is not the mere swapping in and out of alternatives, but, more akin to sedimentary rock, the various fault lines whereby invariances can be observed (this becomes clearer on the next page, below). The core of the argument is set out as hypothesis:

The true constituents of units of a myth are not the isolated relations but bundles of such relations, and it is only as bundles that these relations can be put to use and combined so as to produce a meaning. Relations pertaining to the same bundle may appear diachronically at remote intervals, but when we have succeeded in grouping them together we have recognized our myth according to a time referent of a new nature, corresponding to the prerequisite of the initial hypothesis, namely a two-dimensional time referent which is simultaneously diachronic and synchronic, and which accordingly integrates the characteristics of langue on the one hand, and those of parole on the other. To put it in even more linguistic terms, it is as though a phoneme were always made up of all its variants.

Lévi-Strauss, 1963, p.222-212.

There is a lot going on in this statement. The importance of ‘bundles’ can be apparent when turning to contemporary AI methods, as it is the ability to calculaterelations that is most powerful. Although, there is potentially more to Lévi-Strauss’ account, with its consideration of wider relations, which can help build up a larger sense of ‘meaning’. Similarly, the idea of two-dimensions, or even, as will be noted, multiple dimensions, is again pertinent to modern techniques.

On the next page of the essay, Lévi-Strauss provides a specific example of a ‘score’ when analysing the Greek myth of Oedipus. For the purposes here, it is not necessary to refer to the exact contents of the myth, although Lévi-Strauss’ own human handling of the data is significant. His sorting into the structure shown on the page rises numerous questions. Nonetheless, this page of the essay gives a clear case of how elements of a myth are structured (and weighted) in particular ways, aside from the actual temporal unfolding of the narrative. From a cybernetics point of view, it can be said the constituent ‘units’ (as synchronically set out) are ensured to deliver by the unfolding of the more ‘noisy’ story, and crucially enables it to persist; to keep telling the story, generation to generation.

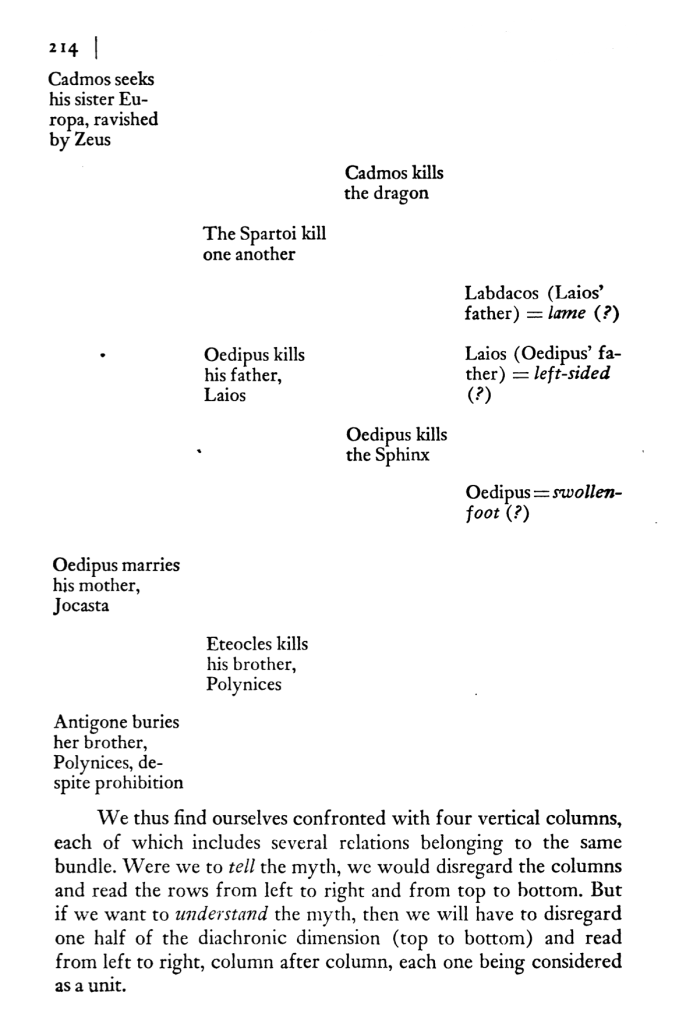

Lévi-Strauss notes the pertinent objection that an analysis can be biased by working only with known versions of a tale. He counters his problem simply with the value of more data, or we might say today, Big Data: ‘…the objection becomes theoretical as soon as a reasonably large number have been recorded’ (p.218). The diagram on this page (Figure 16) is a schematic of the multi-dimensional analysis that ensues. Each variant of a myth will have its own two-dimensional chart (as with the Oedipus example on p.214), but then all of the variants are combined, as in Figure 16, to form a three dimensional set: ‘All of these charts cannot be expected to be identical; but experience shows that any difference to be observed may be correlated with other differences, so that a logical treatment of the whole will allow simplifications, the final outcome being the structural law of the myth’ (p.217). It should hopefully become clearer now, why, in the earlier quote, Lévi-Strauss refers to the need for a special technical setup:

To discover a suitable pattern of rows and columns for those cards, special devices are needed, consisting of vertical boards about six feet long and four and a half feet high, where cards can be pigeon-holed and moved at will. In order to build up three-dimensional models enabling one to compare the variants, several such boards are necessary, and this in turn requires a spacious workshop…

Lévi-Strauss, 1963, p.228.

Or, indeed, today requires only a modest sized computer.

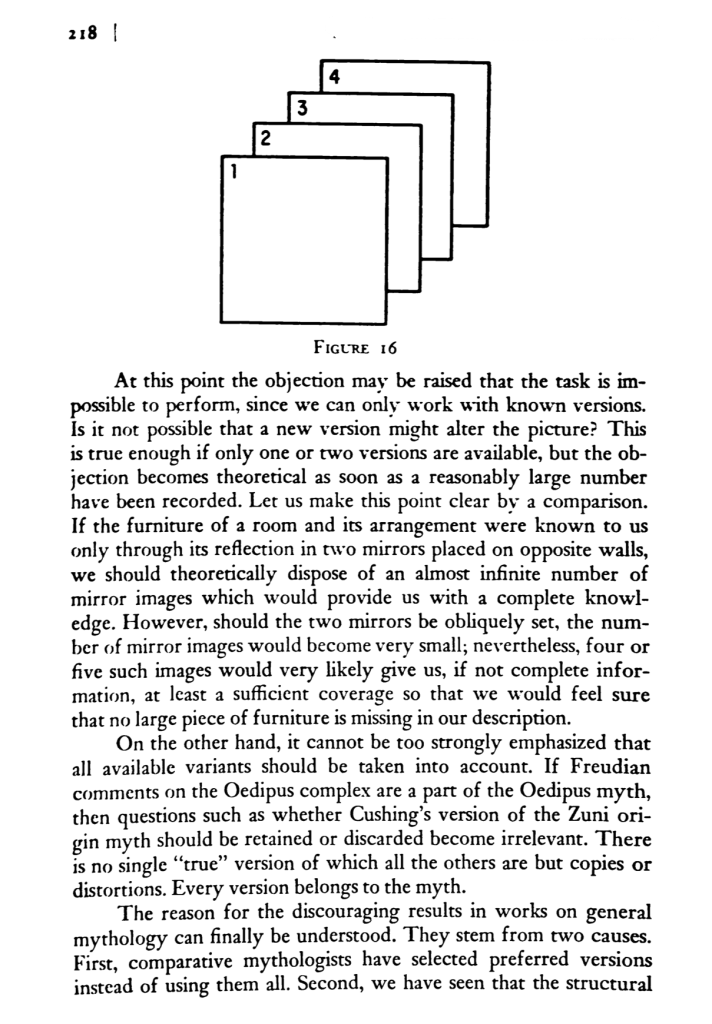

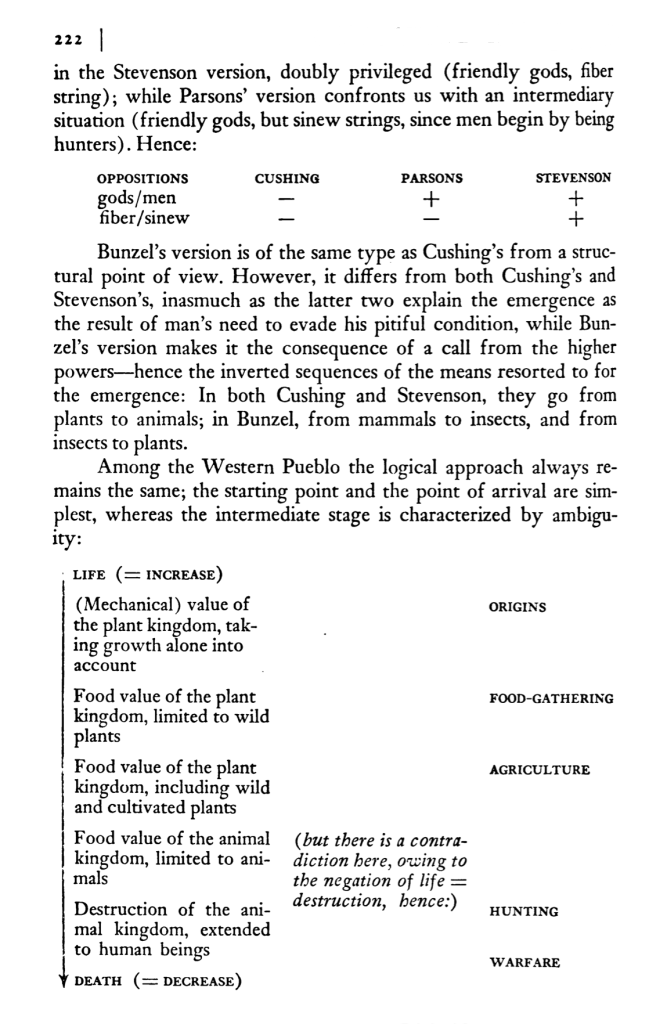

Lévi-Strauss continues with further examples, which on this page shows further ways in which a matrix of results can develop as a series of pluses and minuses (ones and zeros), and with different weightings of double pluses and minuses etc. On the lower half, we see an underlying continuum (life – death) upon which elements are plotted.

Towards the close of the essay, Lévi-Strauss draws out ‘another property of mythical thinking the world over’, namely the ability for ‘contradictory attributes’. Here, he begins to suggest of an approach to compare variants between one context and another, presented in the form of a formula, but which notably makes use not of the equals sign, nor even approximation, but that of the ‘asymptotic equals to’ sign (which I understand is used in computer science in the analysis of algorithms). The formulas on this page lead out to the more general formula (noted earlier):

Despite the brevity and seeming simplicity of such a formulation, it is not easy to fully understand, or test. And, bear in mind, it is supposedly describing complex cultural forms and their equivalences. For now, however, this difficulty might be set to one side, and instead the point to make is that Lévi-Strauss appears to identify specific functions and terms that offer comparison to the contemporary method of Non-Negative Matrix Factorization, which is used for example in our now daily use of image recognition.

Non-Negative Matrix Factorization

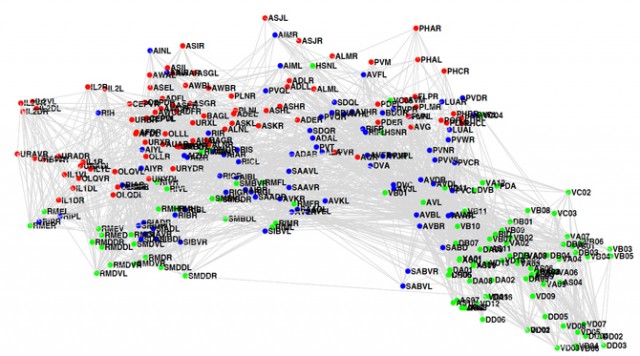

Before turning to the specifics of Non-Negative Matrix Factorization, it is worth noting that the development of artificial neural networks are derived from work on the brain in the biological context of neuroscience. A notable figure is Sebastian Seung, a professor in computer science and neuroscience at Princeton University’s Neuroscience Institute at the Jeff Bezos Center in Neural Dynamics. He is widely known for his contribution to connectomics (Seung, 2012), whereby we need to map not just the structure of neurons, but their myriad connections – a massive undertaking. So far, we have only been able to map the connectome of the worm, Caenorhabditis elegans, with its modest 300 neurons, as shown here (each point is a neuron, each line the numerous connections):

The human brain has nearer to 100 billion neurons, and so far beyond our means of analysis. However, of more specific relevance here is Seung’s related work in computer science. As his staff profile puts it, Seung ‘uses techniques from machine learning and social computing to extract brain structure from light and electron microscopic images’. In particular, he is known for his co-authorship of key articles on Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF). While first introduced by Paatero and Tapper (1994), NMF was popularised by Lee and Seung (1999; 2001), notably for their multiplicative weights update method, which has been widely adopted due to its simplicity of implementation. This technique has gone on to be widely referenced (see: Adrian Colyer’s ‘why and how’) and has become dominant as an algorithmic technique for astronomy, data imputation, text mining, spectral data analysis, bioinformatics, facial recognition, and more besides.

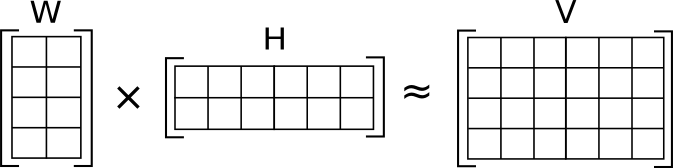

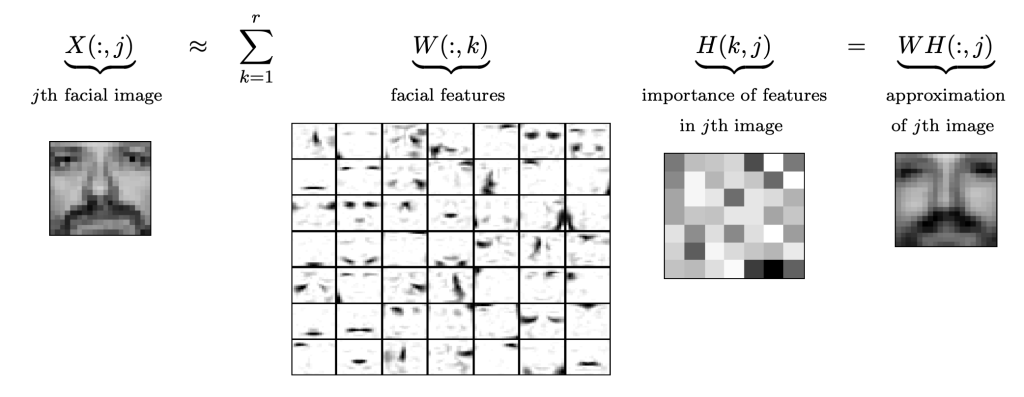

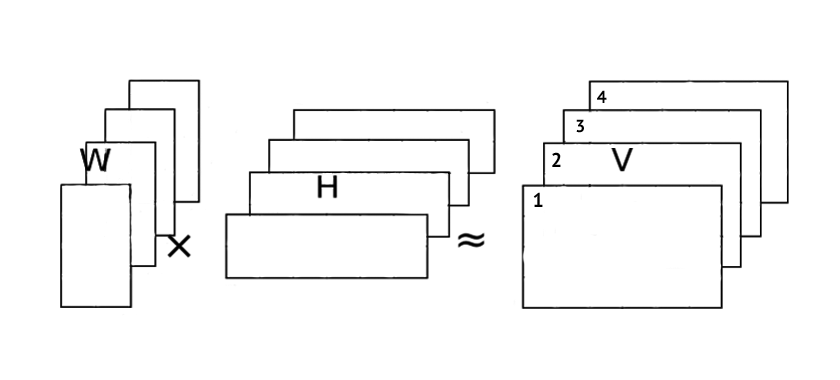

To explain: NMF offers algorithms for use in multivariate analysis. The following diagram shows a matrix V factorised (or grouped) by two matrices or expressions W and H.

The two terms, W and H, could be a range of things, the point being they are in some form of correlation to form a whole(V). They need to be put into combination, or factorised. The ‘non-negative’ element of NMF refers to the need not to compare positions to/from (plus/minus) a mean, but rather to try to approximate actual position. If data is scattered, but suggestive of a pattern across a graph it is possible to draw a mean line through the data, which is then either on the line or appearing some way off, either above or below the line (positive or negative). The mean is not a ‘true’ or actual data point, but rather a virtual one. In NMF the idea is to approximate actual positions. This becomes important, for example, in facial recognition. Rather than plot an average face (i.e. a virtual one, which, according to one study, can be more trustworthy!), the need is to approximate an actual face, to be able to say with reasonable probability that it is x not y. Typically this would mean needing to sort tirelessly through all data points. NMF provides an algorithm to achieve this in the shortest possible time. And, since computers are good at calculations, this can be relatively rapid (rapid enough, for instance, that we do not grow impatient when unlocking our phones with our face).

The following diagram, from Gillis’ (2014), ‘The Why and How of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization’, shows the decomposition of a face database (MIT Center For Biological and Computation Learning). It is followed by a video by Jugal Choksi that works through the various steps for NMF for facial recognition:

There is a great deal more to consider and understand, but hopefully, what begins to emerge are a series of connections and potential trajectories from the work of Lévi-Strauss (working with his limited means of three-dimensional boards) towards the fast evolving domain of pattern recognition and machine learning, notably using Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. However, a really crucial consideration is how Lévi-Strauss chooses to make distinctions between and through the myths he reads. The step he takes to divide up the components of the Oedipus myth, for example, are at his discretion (and meaningful). What is required is an ability to make an informed and contextual reading before the structural reading is then prepared. This suggests of an extended dimensionality.

By contrast, AI technology is typically good at doing one thing, and more significantly fails to ‘know’ why it is doing what it is doing, or to have sense of any intrinsic value. AI can recognise faces on a technical level, but knows nothing of why it need recognise them, nor, once the result is delivered, how a particular face relates to others and other instances in time. AI can predict text, yet does not know why, or what alternative, surprising variations might be made. Crucially, AI remains task-based. It might learn something in new and surprising ways, even in ways out of reach of humans, yet it still amounts to a single operation, as if operating upon a single dimension. What AI lacks is any proper form of contextualisation (and meaning-making), as allows someone, for example, to make the kind of preparatory decisions we see with Lévi-Strauss. As structuralist, Lévi-Strauss is seeking the invariance of myths from around the world. Yet, equally, as anthropologist he is engaged in those myths. Such engagement requires a further layer, or indeed multiple layers, of understanding and ‘processing’. But what if some of the structuralist methodology is applicable?

Two speculations:

(1) The suggestion here for contextualisation, to enable a form of joined-up thinking, might simply be asking too much of current AI methods and technologies; taking us into the realms of agency and artificial general intelligence that seems way off in the future (if at all possible, plausible or even palatable).

(2) There might be envisaged an operation of NMF that extends its dimensionality, that, in emulating Lévi-Strauss’ DIY approach using vertical boards to line up suitable pattern of rows and columns from across variants, it could be possible to determine more of a through-line, to draw together more extensive diachronic and synchronic contextualisation. At the time of writing, Lévi-Strauss thought this required a ‘spacious workshop’. Today, it probably only requires a laptop, although, more crucially, it likely also needs a lot more human collaboration (to draw together an anthropology with an algebra).

References

Graham Allen (2012) Roland Barthes. Routledge.

Barthes (2018) Album: Unpublished Correspondence and Texts, trans. by Jody Gladding. Columbia University Press

Albert Doja (2008) ’Claude Lévi-Strauss at his Centennial: toward a future anthropology’, Theory, Culture and Society, Vol. 25, 7-8), pp.321-340.

François Dosse (1997) History of Structuralism: Volume 1 – The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans. by Deborah Glassman. University of Minnesota Press

Nicolas Gillis (2014) ‘The Why and How of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization’, arXiv:1401.5226.

Daniel D. Lee and H. Sebastian Seung (1999) ‘Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization’, Nature, Vol. 401, 21 October 1999, pp.788-791.

Daniel D. Lee and H. Sebastian Seung (2001) ‘Algorithms for Non-negative Matrix Factorization’, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 13 – Proceedings of the 2000 Conference, NIPS 2000, pp.535–541.

Claude Lévi Strauss (1963) ‘The Structural Study of Myth’, in Structural Anthropology, trans. by Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf. New York: Basic Books, pp. 206-231.

Pierre Maranda (ed.) (2001) The Double Twist: From Ethnography to Morphodynamics. University of Toronto Press.

Paatero and Tapper (1994) ‘Positive matrix factorization: A non-negative factor model with optimal utilization of error estimates of data values’, Environmetrics, Vol. 5, Issue 2., pp. 111-126.

Sebastian Seung (2012) Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are. Penguin.